You Give Me Bad Dreams

Don't drop in next time you're passing

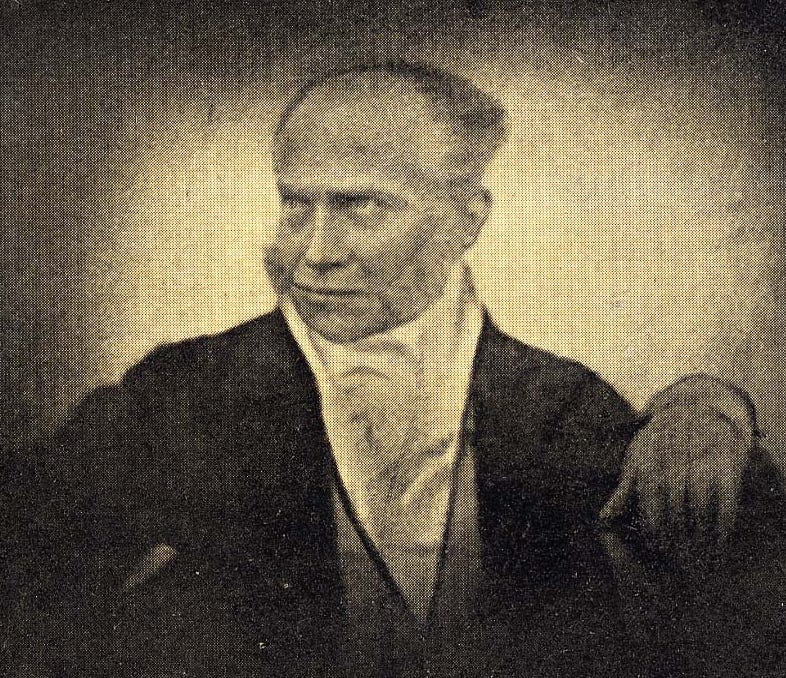

In 1807 Johanna Schopenhauer wrote a letter to her nineteen-year-old son Arthur, telling him that he was not welcome in her home. As quoted in Wilhelm Gwinner's Arthur Schopenhauer, aus persönlichem Umgang dargestellt (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1862), pp. 26-27 (my translation):

In order to be happy I need to know that you are happy, but I do not need to see it first-hand. I have always said that it would be very difficult to live with you, and the closer I observe you, the greater this difficulty appears to be, at least to my eyes. I make no secret of it. As long as you are the way that you are, I would rather make any sacrifice than come to this decision [i.e., to tell him to stay away]. I am well aware of your good points. I am not shying away from your nature or inner qualities, but rather your outward manner, your opinions, your judgements, and your habits. Simply put, I cannot share your views about anything that concerns the outside world. Your moroseness, your complaints about things that cannot be avoided, your bizarre judgements which you pronounce like an oracle without allowing anyone to speak against them — these things oppress me and ruin my good humour without being of any benefit to you. Your nasty disputations, your lamentations over the stupidity of the world and human suffering disturb my nights and give me bad dreams.

Subhead courtesy of Elisabeth Welch.

The quiet suffering endured by the mothers of German philosophers has gone unappreciated for far too long. Thank you for doing your part to memorialize their thankless patience!

This is hilarious. NOBODY can stand Schopenhauer’s company.