A Great Painter's Art Lessons, in English After a Century

Lovis Corinth's handbook for art students

Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) bridged the academic and the modern, developing a style that was somewhere between Impressionism and Expressionism. He was one of the most important members of the Berliner Sezession and one of the city’s most fashionable portrait painters, so I was surprised to find that his book for art students has never been translated. I guess Bob Ross cornered the market.

Here are a few excerpts from Corinth’s Das Erlernen der Malerei (Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1909), my translation:

It is generally assumed that people who wish to devote themselves to painting have an innate ability to do so. People call this ability talent. It shows itself in early childhood, and later in life it helps the poor to overcome their poverty, since the joy of creation renders all adversity insignificant. For the rich, conversely, this talent and joy in creative work may prevent them from frittering away their money in mere dissipation.

A professor in southern Germany once remarked, and he was not entirely wrong, that it takes three things to make a good painter: talent, industry, and money. You might lack one of these, he said, but never two. In other words, one must possess talent and industry, talent and money, or industry and money.

The creation of a work of art (a picture) requires the study of two subjects:

drawing

painting

There must also be further theoretical lessons in:

perspective (a sense of space and proportion)

human anatomy (clarity of construction; bone and muscle theory)

art history (studying pictures from the past in order to build on them)

Students of painting will approach the art in their own fashion. Their differing approaches are due to personal individuality.

The more talented an artist is, the more singular his perception (individuality) will appear to the public. The masses will not understand him, so his work will go unrecognized for the foreseeable future and will find no buyers. He must assert himself and compel recognition; then his fame will be all the greater and will endure beyond his death. Many an artist has only been honoured posthumously, by a better generation.

In this manual I treat chiefly of drawing and painting. The student must seek theoretical instruction in the other three subjects elsewhere, whether in books or schools.

As stated earlier, you should note how the individual parts of the head stand in relation to one another: the length and breadth of the forehead, how the eyes sit beneath it, as well as the length of the nose, the mouth, and the chin. Then observe how the major areas relate to each other in size. Consider how the area from chin to eyes compares to the forehead, and so on. It is best to begin drawing from the centre, say with the position of the eyes, and then add the rest. Besides comparing the relationship of the elements to one another, you must also determine which points of the various features lie forward or back, lower or higher.

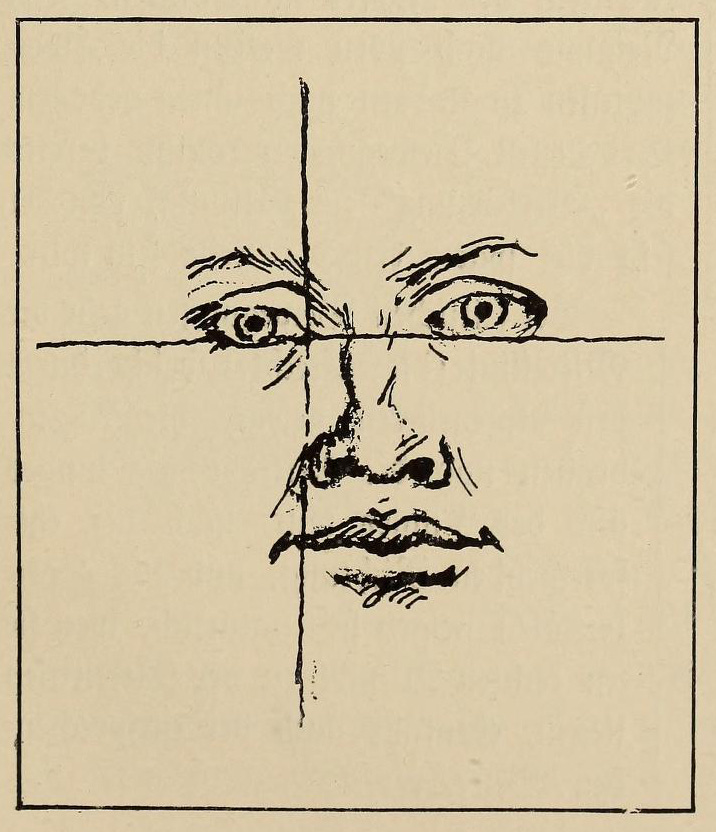

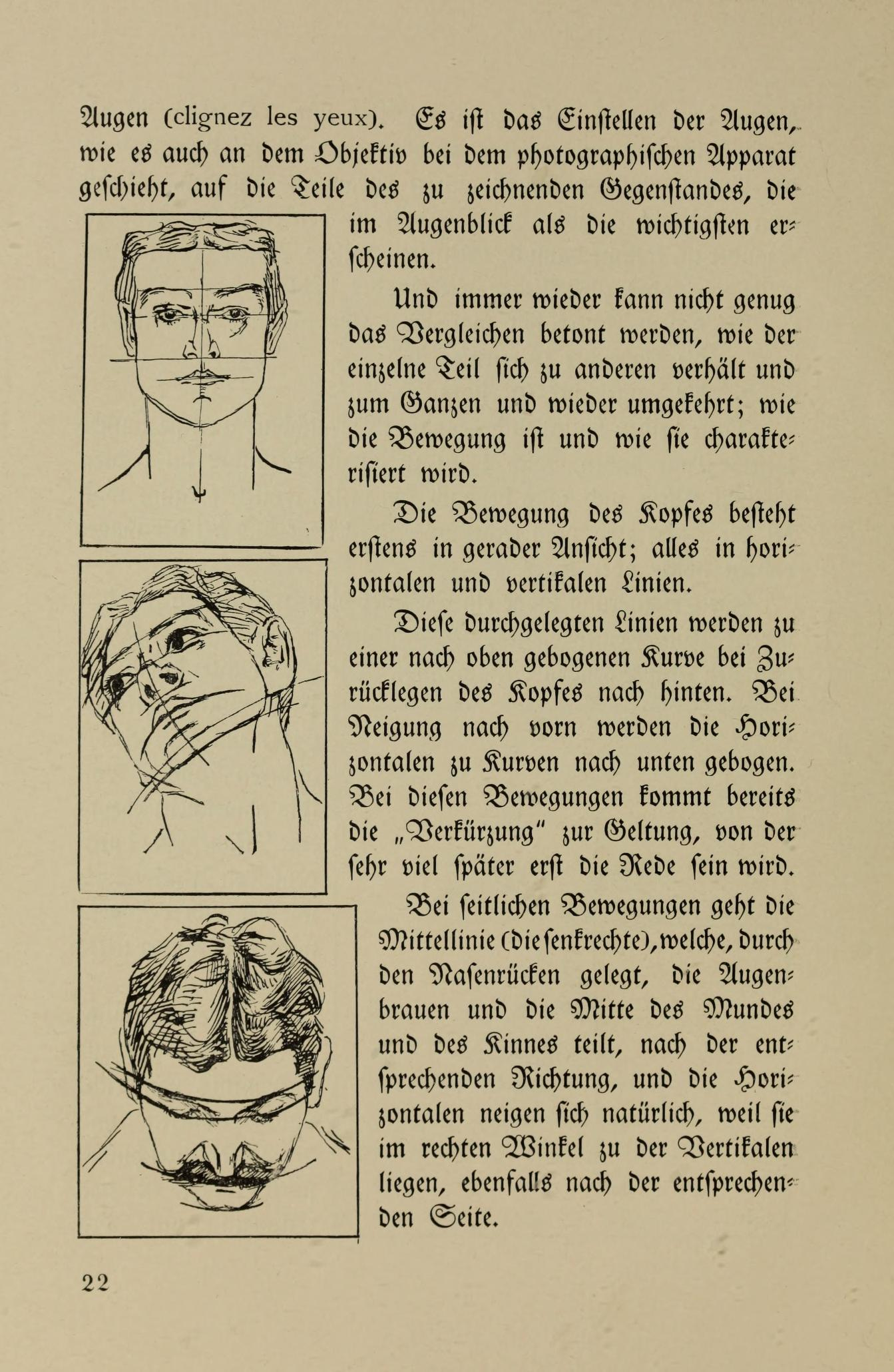

For this purpose you have two essential guide lines: the vertical and the horizontal. These two lines are invaluable because they never shift and always meet at right angles. The vertical shows you what lies to the right or to the left; the horizontal shows you what stands higher or lower.

An example will make this clear: Take the inner corner of an eye, the edge of the nose, and the corresponding corner of the mouth on the same side of the face. Drawing a vertical line through the corner of one eye shows how much the other points deviate from it; similarly, a horizontal line drawn through that same corner shows how much higher or lower the corner of other eye stands.

To recognize patterns of light and shadow clearly and draw them accurately, one important technique is to squint or, as the French say, clignez les yeux. It is adjusting the eyes, like a camera lens, to focus on whichever parts of the object seem most important at the moment.

I cannot stress this enough: compare the various elements, and understand not only how one part relates to the others and to the whole, but also see what the movement is and how it is expressed.

The sockets, which lie beneath the frontal bone, house the eyes. These are surrounded by a ring muscle forming the upper and lower lids, both with lashes. The opening of the ring muscle determines the shape of the eye — whether it is large or small, round or elongated. Then there is the eyeball with its iris and pupil. The inner and outer corners of the eye rarely sit at the same angle. When the outer corner is higher, the eye takes on a slanted, almond-shaped look; when the inner corner is higher, the expression turns gentle, as one sees in a dog.

Indeed, it is worth noting that some part of the human face often resembles that of an animal: some faces call a bird to mind, a long hooked nose suggests a ram, and a puffy fat face with small eyes makes one think of a pig. Such observations should be cultivated diligently, for they reveal the subject’s character, and work that reveals character is always a praiseworthy thing.

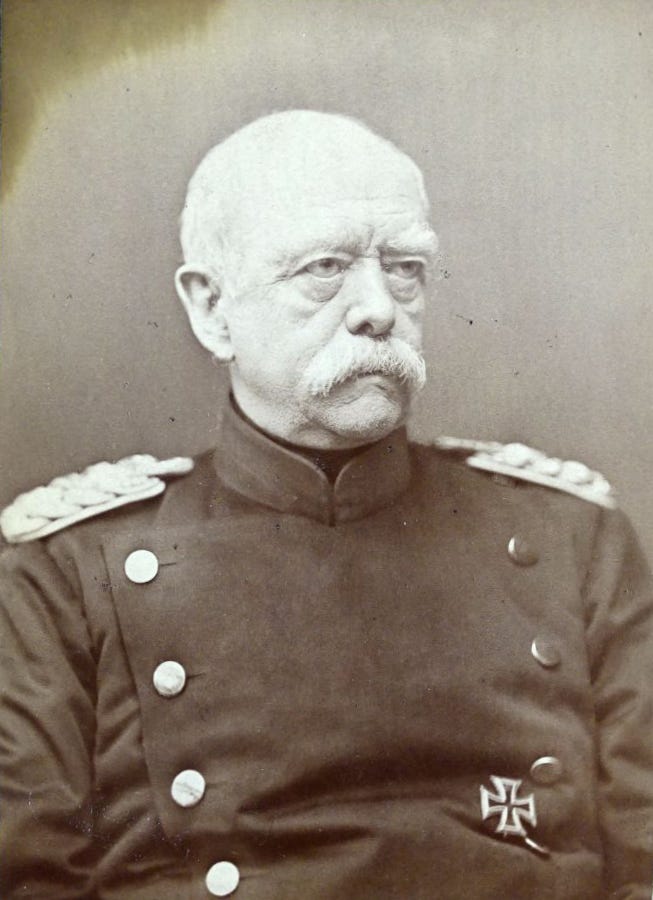

The nose will be hooked or straight, depending on the shape of the nasal bone. The nasal bone and its cartilage form the bridge of the nose and, on either side, the nasal walls. On the underside of the soft tip sit the nostrils and the flared sides of the nose. The tip of the nose may be bulbous and thick, or fine and pointed; when it is large and prominent, it sometimes has a visible cleft down the centre. When a short nose is combined with a squat face, one is reminded of a bulldog; Bismarck was a striking example of this type.

This is just the beginning. There are 25 lessons in the book. Subscribe below and each new translation comes straight to you.

The Obolus Press publishes the kind of books you won’t find anywhere else: works that have never been translated into English, literary and philosophical texts that have fallen out of print, and monographs about neglected European artists.

Recovering what mainstream publishing abandoned. We sell directly to readers, not through Amazon. Order at www.oboluspress.com