Prison and Deportation, #05

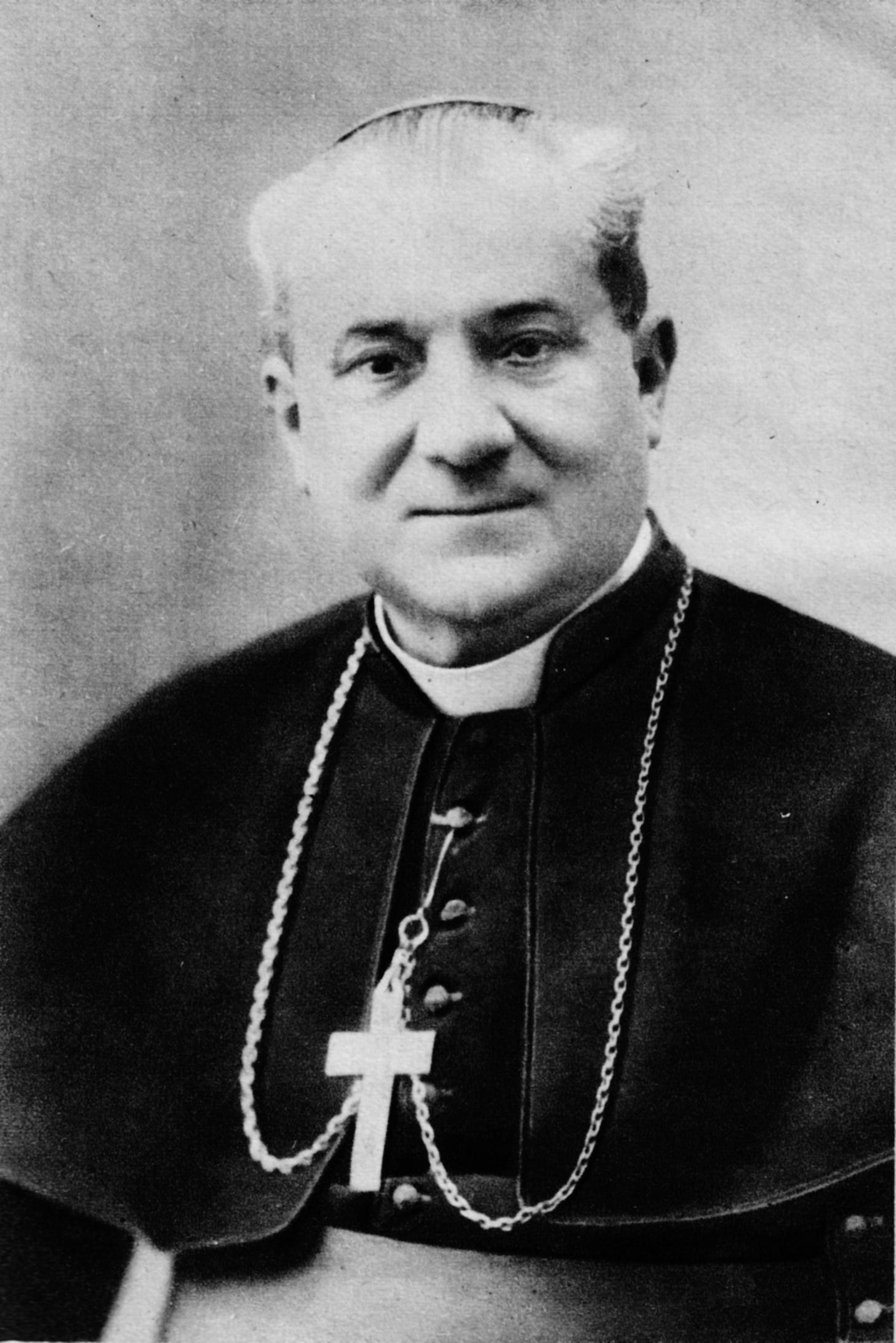

Msgr. Gabriel Piguet's Memoir

This is an excerpt from my translation of Msgr. Gabriel Piguet’s memoir Prison and Deportation. If you would like to read the rest of the book, you can order a copy here. You will find other excerpts here.

Next week, I will begin posting excerpts from my translation of Marius Vachon’s monograph about the painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905).

Chapter 7

Arrival and the Revier

The order to evacuate the Natzweiler camp was given, or at least put into action for the first time, on the night of Friday, 1 September. For three days, successive columns of prisoners were taken to the Rothau station and put on trains. Those in the infirmary were part of the convoy of Monday 4 September; they were placed in livestock cars, where the sick could lie on mattresses. It took two and a half days for us to make the journey between Rothau and Dachau via Munich. Hunger and thirst were already beginning to make themselves felt. We arrived at Dachau station after dark. At midnight, we were hauled to the camp by truck. In the shadows, its wide alleys had a certain allure. We, the sick, were laid outdoors in the large square where we were to spend the night, waiting for them to make room for us inside. It was a strange night, and the weather had already turned cold in this camp that was situated on drained but always damp marshlands! Fortunately we were warmly dressed, wearing clothes that the camp authorities had taken from other deportees and distributed to us before we left, and which would later be collected from us and replaced by old rags.

Changing clothes was a frequent exercise in the concentration camp; what detainees wore did not have to be official or standardized. The word “organising” was common in Natzweiler and Dachau, and it meant “getting by”, usually with the connivance of someone in charge of the supply room. In prison conditions this “organisation” was certainly not synonymous with theft, given that the deportees were not able to reclaim most of the things that had been confiscated from them, and how far removed their living conditions were from what they were rightly entitled to have.

During this night “under the stars”, I gave absolution to a sick priest who had been wounded at the outset of the war, and had fainted. I was afraid that he would die before dawn. It was, alas, something that was commonplace in the hell of the camps and the terrible transports which were the scene of the worst horrors.

In one convoy from Compiègne to Dachau, over 2,000 prisoners died, 900 of them from asphyxiation or insanity due to lack of air and the oppressive summer heat. Abbé Goutaudier, a confrère and friend of mine from the diocese of Autun who was also deported to Dachau, was a witness to this, as were several of my diocesan colleagues who arrived on this train. People often recalled this grim event in Dachau.

Another transport to Mathausen consisted entirely of men whose clothing had been taken from them, as punishment for a few escapes along the way. Clothes were distributed to them haphazardly when they arrived; for the part of the journey they were required to make on foot, some of the taller men had to wear small suits and the shorter ones were stuck with trousers that were too long.

The isolated deaths and fainting spells caused by lack of care were minor incidents compared to the dark tragedies and burlesque scenes that killed or crushed people through ridicule and degradation.

At the start of the morning, after daybreak and roll call, the prisoners who acted as secretaries came to “register” us. A change of camp meant a change of number, so therefore a new registration. This time I became number 103.001. The priests who were detained in Dachau had already been alerted by the first arrivals from Natzweiler and knew in advance that I would be in this convoy. Several watched for me and came to greet me with deferential sympathy. Among them was one of my vicars from Clermont, Father Clément Cotte, who had volunteered to accompany young French workers to Germany so as not to leave them without spiritual aid. His zeal and contempt for danger eventually led him to Dachau.

It is always a joy to meet with priests and friends, even in common misery.

For me, this particular morning was full of contrasts; on one hand there were the surreptitious greetings and friendly encounters I had with the priests, and on the other there was the casual treatment (to put it mildly) I received at the hands of those in charge of the camp and the infirmary. They did not seem to consider that we might be cold. What was the point? Those in power had made suffering the law. The death that followed for many was the destination towards which all deportees, sooner or later, were to be routed.

My memories compel me to make these observations, and I wish to do so for three reasons.

First of all, Germany, even when it disassociates itself from the Nazis, must not forget that it has much to repent — people should not be treated this way.

Secondly, all of the nations that hold Germany accountable must also take care to respect the human individual and not to infringe, under any pretext whatsoever, upon the respect due to man.

Finally, in the face of the ever-increasing authority of the modern totalitarian state and the practices of cruel police forces with unrestricted power, it is essential that we reaffirm the rights of the individual and the precarious state of mankind whose position can quickly change from tyrant to victim.

My stay in Dachau was to last eight months, divided into three periods: three weeks in the infirmary, four months in the priests' block, and three months in the camp prison.

The concentration camp infirmary or hospital, known as the Revier, bore all the hallmarks of cruelty and hypocrisy typical of the Nazi system.

It was here that so-called scientific experiments were carried out on men who had become guinea pigs. A German priest, a companion who was always eager to help me with the sewing that I could not manage very well, assured me that he had been given the malaria virus. “If I were sick to death, I would never go back to the Revier for treatment,” he said. People did not always die at the Revier, but many would have done well to follow this German priest's advice and avoid going there in the first place. But what do you do when you are at the end of your tether and it is the only way to get some rest?

This was my case; I was not ill, strictly speaking, but I was literally exhausted, with a slight fever at times. Like many of my companions I had liver problems, which was result of the living conditions. It could mean death in our unfortunate circumstances.

Throughout my stay at the Revier it was my good fortune to have General Delestraint as my bunkmate. He was a wonderful man who distinguished himself with his deep Christian faith, his ardent love of country, and his selfless dedication to the Resistance.

Our proximity meant that illustrious visitors came every day — friends the General had made at the Natzweiler camp, as well as my diocesans. There were doctors, Professors Chaumerliac and Limousin from the Clermont-Ferrand medical school, and Doctor Roche from Thiers, with whom I maintained the most cordial relations, and so many others whose memories I hold dear. It was not always easy to meet. The entrance to the Revier was locked, and you had to be resourceful to make it over the thick bulwark of regulations... A deportee's stratagems, like the demons mentioned in the Gospel, were legion.

With the connivance of some of the doctors, nurses, and other prisoners, the Blessed Sacrament was smuggled into the infirmary. I was able to take Communion every day, and I myself offered Holy Eucharist daily to those who wanted it. The strength of the Host was desirable and beneficial to us.

We had to employ incredible subterfuge in order to distribute and receive Communion.

We used to bend down together from our bunks as if to pick something up from the ground. The communicant would then make a gesture with his hand to hide his mouth from the many curious onlookers. I would then give him the Sacred Host without anyone being able to see anything. We had everything to fear if the anti-religious, harassing, and cruel authorities had noticed the distribution of the sacrament. It was done in secret, and far surpassed the advice in the Gospel, which recommends one close the door of one's room before beginning to pray.

There were so many moments of thanksgiving and union with Christ among these faithful men who were enduring a time of trial. They withdrew into secret and intimate sanctuaries more secluded than their own rooms, because it was in their hearts, in their minds, that they silently found and communed with God.

Another amazing aspect of the Revier was its organisation. As with the other services, the prisoners ran it under the constant control and direction of the SS, the police, and a German head doctor.

But the doctors' duties, like those of the priest, were a source of conflict with the Nazi authorities; they eliminated the priest's role in communal life and he was lost in the crowd. The concentration camps often used doctors, but not always, since some of them had been mixed up with and absorbed into the mass of common workers. Those who were employed professionally were placed under nurses, bricklayers, hairdressers, and carpenters. Their science and art had to be dominated by the authority and incompetence of their nurse, who thus preserved the prestige of the enemy Nazi authority and kept them from being exposed to any moral, professional, or simply human excellence.

☞ This book remained untranslated for more than 75 years. If you would like to help me bring other neglected titles to English readers, you can leave a tip with PayPal:

When I left the infirmary after three weeks, my discharge was based on the decision of the room nurse, confirmed by the block nurse, and ratified by the head nurse, a German whose doughy appearance justified his bad reputation. My doctor, a Pole, not at my request but of General Delestraint, acknowledged that I still needed rest, but declared himself unable to extend my time in the infirmary. “All I can do,” he told the general, “is provide the bishop with a powder that will give him a fever and probably allow me to readmit him after he leaves.” The bishop, however, considered that his misery was great enough without adding to it and seasoning it with a fever-inducing powder. Once again, he preferred to leave things in God's hands.

The subordination of doctors to nurses was such that, on another occasion, a renowned French surgeon dropped down on the end of my bunk and said these simple words to me: “This time, Monseigneur, it is the limit. My nurse will only allow me to do small dressings; they are keeping the large, important ones for themselves.”

Another French doctor who was a very distinguished specialist in lung diseases at home confided to me that he used to only perform a pneumothorax in very rare cases, when he had determined it to be appropriate. At the camp they forced him to do one after another because that was what they wanted done.

Eye infections were common in Dachau, and an eye doctor was of tremendous help. He was reproached by his nurse for not always treating them by the book. As a good practitioner, as well as a good citizen of Auvergne, the doctor replied that his experience had taught him a great many things that were not in the book. He was able to continue his treatment according to his diagnosis and to the benefit of his numerous clients, victims of the dampness at Dachau.

The administration of the infirmary was overseen by SS doctors. There were still doctors in Germany with a reputation for knowledge: they were from the previous generation. The young doctors, trained since the advent of Nazism and put in charge of our camp's medical service, had a well-established and, it would seem, justified reputation for having more medals than medical knowledge: A long war had torn medical students away from their universities, as it had done in other fields of study, and the school curricula in Nazi Germany had debased intellectual and scientific standards by overloading courses with racial theories and standards. Fallacy is essentially destructive. If people have a little sense, they will remember how scientific standards at German universities declined under National Socialism.

I would like to add a remark about the way care was provided in the concentration camp's infirmary.

A colossal amount of paperwork went into registering the patient, diagnosing the illness, compiling files, etc. At Dachau, everything was ordered to be burnt before the Americans arrived. What a pity! When you first looked at the files you would have thought that no one on earth had ever been treated as well as these unfortunate deportees, who died like flies...

There is no doubt that they received every procedure that modern technology could provide. They were weighed, x-rayed, their blood pressure readings were taken, and so on. But in fact it was the patient's medical sheet, where all this information was recorded, that received treatment — not the patient himself. He was exposed to the cold when he waited his turn at the X-ray or somewhere else. If he went in with simple pneumonia, he would come out with double pneumonia that was contracted during a long wait outside the door of the operating theatre where he was force to stand, barely dressed, shivering in the cold and with a fever. The sadism of duplicity and hypocrisy, so typical of the way things were done there, was on full display in the medical field, just as it was in every other area, from sports to all the activities of daily life.

As I said earlier, I was discharged from the infirmary on Friday 22 September. For the third time I received a suit that was new to me, but certainly not new! A patient, a former officer in the Austrian navy whom I did know know, said to me: “God will recognise the humiliations that have been inflicted on you.” I had already suffered worse. With striped uniforms or unstriped old clothes, ridiculous in size and colour, with letters painted on the backs of jackets or the sides of trousers — it was a sinister buffoonery in the most comical and, alas, the most tragic of masquerades. But when you were not too cold, it was easy to resign yourself to it. Physical “resistance” has limits that the “resistance” of the soul does not know. Not everyone can be degraded.

To read the rest of Msgr. Piguet’s memoir, click the button below: