The Contract Between Artist and Public

You don’t expect to understand anything as important as art straight off, do you? I mean, this is pretty complex stuff.

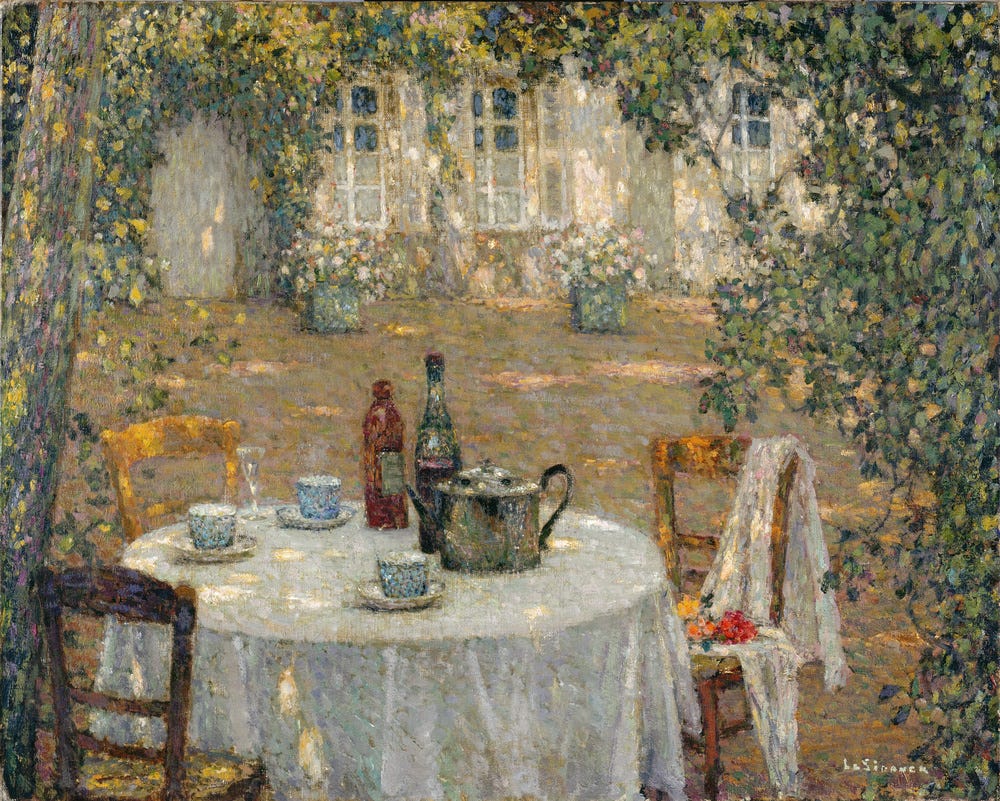

Camille Mauclair, Henri Le Sidaner (Paris: Georges Petit & Henri Floury, 1928), p. 192 (my translation):

Believability has always been the necessary condition for an exchange of understanding and emotion between the artist, his work, and the public. If a picture does not remain believable — even if it is obviously interpreted along certain predefined lines — and if a creator declares that he alone possesses the absolute right to understand his thoughts while at the same time he persists in looking for validation from others (for he does, after all, exhibit his works), then the terms of the natural contract have been broken. We cannot replicate life literally, nor is it desirable that we should do so; all the images we assemble are arbitrary in that they remain approximations — it is a question of whether they are approximations to a greater or a lesser degree — but when the artist leads us somewhere, we must always be able to believe the scene and breathe the air. Without this, the work will be childishly incomprehensible no matter how profound a meaning it is supposed to contain.

Cf. Philip Larkin in the introduction to All What Jazz (London: St. Martin's Press, 1970):

I am sure there are books in which the genesis of modernism is set out in full. My own theory is that it is related to an imbalance between the two tensions from which art springs: these are the tension between the artist and his material and between the artist and his audience, and that in the last seventy-five years or so the second of these has slackened or even perished. In consequence the artist has become over-concerned with his material (hence an age of technical experiment), and, in isolation, has busied himself with the two principal themes of modernism, mystification and outrage. Piqued at being neglected, he has painted portraits with both eyes on the same side of the nose, or smothered a model with paint and rolled her over a blank canvas. He has designed a dwelling-house to be built underground. He has written poems resembling the kind of pictures typists make with their machine during the coffee break, or a novel in gibberish, or a play in which the characters sit in dustbins. He has made a six-hour film of someone asleep. He has carved human figures with large holes in them. And parallel to this activity (“every idiom has its idiot,” as an American novelist has written) there has grown up a kind of critical journalism designed to put it over. The terms and the arguments vary with the circumstances, but basically the message is: Don’t trust your eyes, or ears, or understanding. They’ll tell you this is ridiculous, or ugly, or meaningless. Don’t believe them. You’ve got to work at this after all, you don’t expect to understand anything as important as art straight off, do you? I mean, this is pretty complex stuff: if you want to know how complex, I’m giving a course of ninety-six lectures at the local college, starting next week, and you’d be more than welcome. The whole thing’s on the rates, you won’t have to pay. After all, think what asses people have made of themselves in the past by not understanding art — you don’t want to be like that, do you? Keep the suckers spending.

Very nice. And that Larkin passage is fantastic.