The Weimar Stock Market

People speculated on everything...

In A Moral History of the Inflation, Hans Ostwald (1873–1940) describes how loose monetary policy in Weimar Germany helped to fuel speculation in the stock market. From pages 69-71 of my translation:

The stock tip was king in those days. Everyone paid hommage to it. Evenings in the pub, mornings in the barber shop, on the bus and on the suburban railway — there was always a stock market sage somewhere, offering his tips. If he had ties to big business or a bank manager, his words were regarded as divine prophecy, even if his relationship with the bank manager was only that of a clerk or a typist. Indeed, there were women who knew exactly what was going on in mining stocks. And the lovers who talked of securities between kisses also gave the best tips: I. G. Farben, Zellstoff, or Sarotti. In those days everyone knew which stocks to buy.

This was not constant throughout the inflation years, however. There were lows and plateaus between bull markets. When the markets were on an upswing, then all was well again. Take the fall of 1922 for example, when a medium-sized bank received 50,000 orders on a single day. The stock exchange had to take three days off to give the banks enough time to process the public’s orders. People speculated on everything — it did not matter if they were chauffeurs, starving homeowners, artists, or accountants. The share prices went up, though not always as much as the price of other things, such as food, for example. At the end of October the price of butter rose by 50 per cent, but stocks only increased by 20 per cent. From early 1922 until the autumn of that year, the price of stocks on the exchange rose two and a half times, but the value of the US dollar increased twentyfold during that period, and goods were twenty-five times more expensive. So businessmen and producers were more secure than speculators! Then things resumed their upward swing again, as one young man described in his rapturous account of those days:

The inflation, you could really live then! Time was on our side. I had no worries, so I did not need to think much. I used to take a thousand marks to the bank in the morning — not too early, though, since you’d have a good sleep first. It was always late in the morning … So with a thousand marks you’d go to the bank and place an order to buy four hundred marks’ worth of shares. In those days you only needed to put down a 20 or 25 per cent deposit! … The bank would buy the shares. And one or two days later there were shares in my account worth six, eight, or even ten or twelve thousand marks! Then you only needed to sell off a small portion to balance the account. The bank would have its four thousand, and I had four or six thousand left over. Well, then you’d put in another order to buy, and in a few days the stocks would go up again — it was easy to make up the difference to the bank from the gains, and I still had a nice balance in my account.

That was all you needed to do then, just go to the bank in the morning. Well, perhaps take a quick look at the financial papers once in a while.

“Oh, even that wasn’t necessary!” said one older man. “The stocks went up anyway — they did the work for us!”

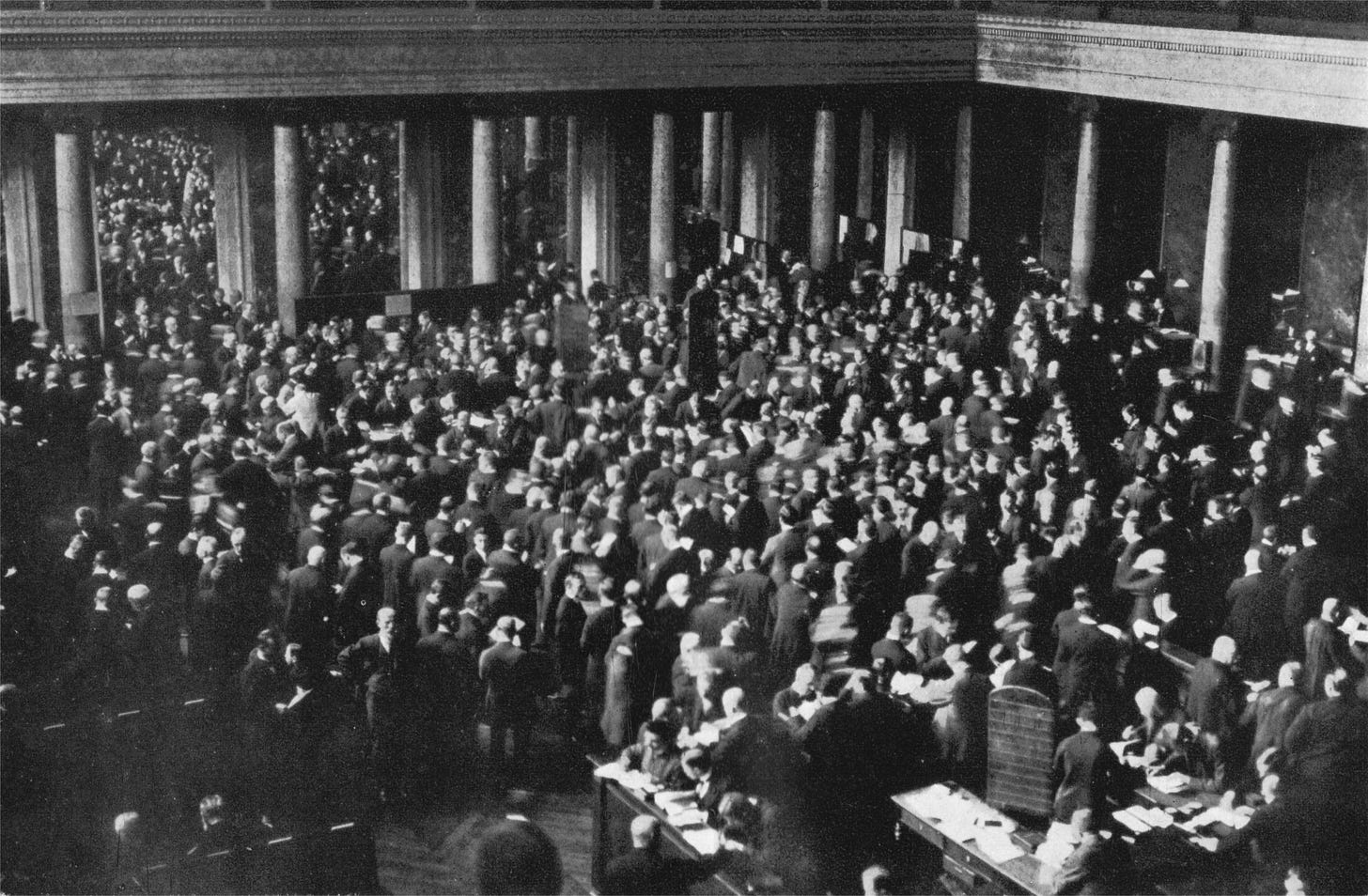

“The only unpleasant thing was sometimes the crowd at the bank… Didn’t everyone run to the bank? Didn’t you have shares too? Ah, the paper stock certificates were so beautiful. Rudelsdorf, Simpelline, and Zellstoff…’

“Well, I did not buy such elegant stocks,” said the older man. “At first I always used a portion of my salary to buy shares in several smaller firms. I sold them off bit by bit over the course of the month. My family and I were always able to live off the proceeds of each share for several days.”

“Yes, those were the days!” exclaimed the younger man. “I lived like a king! Like a king!”

“Well, I didn’t have it bad either,” said the older man.

“Well, you could have purchased larger shares. They rose even more quickly. There was really something left over after you sold those! It did not matter what you bought. You didn’t need to put in much mental effort… We lived, oh how we lived! Every night, every night! Always on the move. The finest and most expensive things! I lived like a king, like a king!”

This way of life and leisure was only possible thanks to credit: The banks gave it to the customers, and the Reichsbank provided it to the banks. In the early fall of 1922, banks were given a substantial portion of the 100 billion marks that had just been printed. The money was originally intended to stimulate the economy, but more than anything it encouraged speculation.

If you would like to know more about this book, you can watch this brief video or read this review in the Times Literary Supplement (paywalled).

I have a few “imperfect” hardcover copies on hand that I am selling at 25% off; the text on the spine was printed a little too high, otherwise the book is fine.

Just enter IMPERFECT in the coupon code box during checkout:

If the IMPERFECT coupon code stops working, it means I’ve sold them all.

Note that, under the USMCA, Canadian books remain exempt from tariffs. American customers will not face any additional taxes or fees.