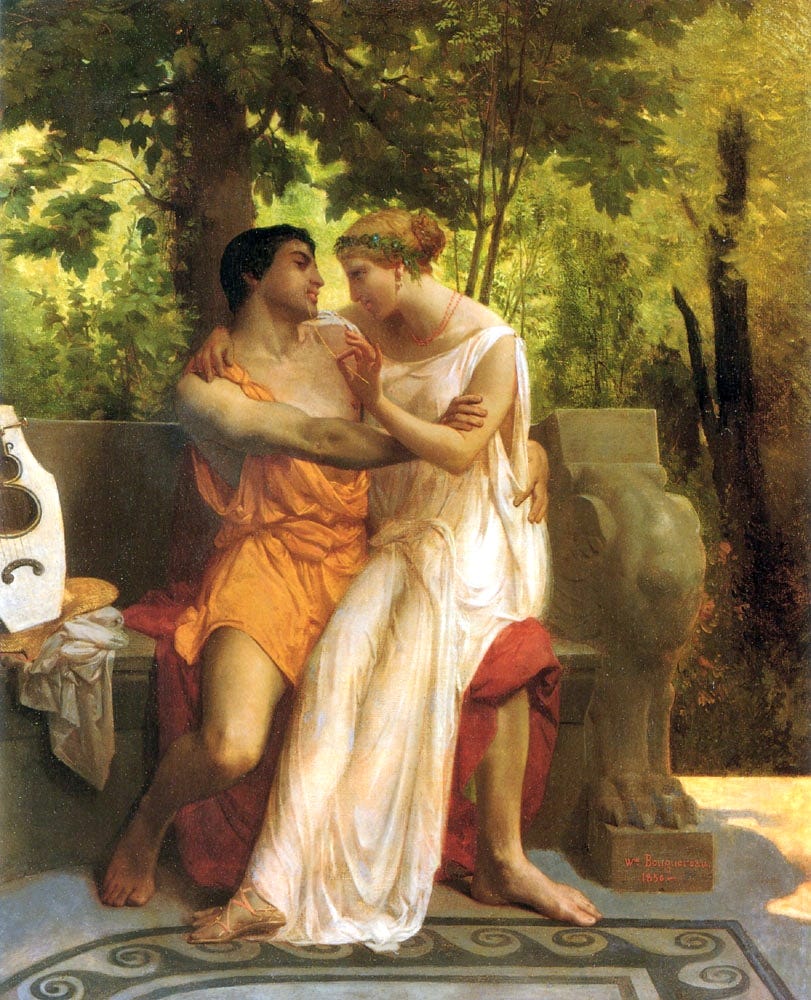

William Bouguereau, #01

A Contemporary Biography, by Marius Vachon (1850–1928)

Marius Vachon’s biography of William Bouguereau was published in 1899 by Alexis Lahure (1849–1928), a printer with offices close by the Luxembourg Garden in Paris at 9, rue de Fleurus. As far as I know it is the sole contemporary account of the painter's life, which is why remarks about and from the artist are in the present tense.

What follows is the initial excerpt from my translation (an uncorrected first draft). You can find all of the instalments here.

Chapter 1

Early Life

William Bouguereau was born on 30 November 1825 in La Rochelle, the son of a well-established bourgeois family. Some of his fore-bearers held important positions in the city, where they were goldsmiths and assayers. There is a file of handwritten biographical notes in La Rochelle’s municipal library which contains the following unpublished account of his ancestors:

The Bouguereau family, which still lives in La Rochelle and remains Protestant, has lived in this city since the first half of the sixteenth century, and they appear to have been early supporters of religious reform. Marie Bouguereau, who was baptized by Pastor Jacques Merlin in 1601, was the daughter of Allaire Bouguereau, who had married the goldsmith Jean Delaizement in April 1624. Delaizement’s son, Daniel-Henri, became a pastor in 1668 was appointed minister in La Rochelle in 1684; he and his protestant colleagues shared the same trials, prisons, and exile. Marie had two nieces, Madeleine and Anne, who were the daughters of the goldsmith Macé Bouguereau. The former married the pastor Elisée Beauvel and the latter married Jacques Fontaine, who was pastor at Royan. Both left France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Anne’s sons, Peter and John, also became clergymen; one served as minister at Royan but abjured his religion at some point before 1680 while the other married Estlier Hoissard in 1671. This latter son appears to have remained pastor of Saint-Surin d’Uzu until the Revolution. Macé’s descendants continued to serve as officials of the Monnaie until after 1787.

Bouguereau’s father was a Catholic and one of his uncles was even a priest in the small village of Mortagne-sur-Gironde, but his mother was a Protestant. In accordance with the marriage conventions of the time, the son born of their union was raised in the father’s religion; he spent his early childhood at La Rochelle and remained there until 1832, when his father, who was a wine merchant, moved to Saint-Martin-de-Ré. In an artist’s life, childhood impressions are the most enduring, and the most intense; they almost always have a decisive influence on temperament and character. Bouguereau has retained a deep affection for his place of birth. He loves and admires La Rochelle with all his heart, with all his soul. He praises, enthusiastically and sincerely, the town’s original and picturesque beauty, its mild and healthy climate, and its breezy, bright, and invigorating atmosphere. He is proud to recall the city’s venerable history, the famous siege, and the intrepid sailors and daring merchants who left to make their fortunes in Canada, South America, and the Indies. With its charming scenery — the old towers that stand guard over the water, the white, blue and pink houses, the quays, the monumental city gates and its bell towers — Bouguereau believes that La Rochelle is the most beautiful port in the world. When the setting sun lights up the sails and multicoloured hulls of its fishing boats, the spectacle equals or even surpasses the ones that painters and poets have celebrated in the classical settings of the Mediterranean and the Orient.

Bouguereau's family moved to Île de Ré, and he continued his education at the elementary school in Saint-Martin-de-Ré. By that time, he had already demonstrated a marked aptitude for drawing. He filled his notebooks and his sketchbooks with landscapes and seascapes, with sketches of sailors and peasants; he excelled in carving all kinds of rustic farm implements and boat hulls out of wood and soft stone with a knife. Some of his friends religiously preserve these works as souvenirs of their childhood.

Once he had completed his elementary schooling it was decided that, given his exceptional intelligence, he should pursue higher education. His uncle, the curé of Mortagne agreed to take him on and teach him the fundamentals of Latin. The boy was delighted. Fifty years later he wrote a moving letter to the old man, relating the memories he had retained of his arrival and his first day in the village:

I can still see myself making the trip from Saujon to Mortagne, sitting on the horse behind Drouillard. I remember how cold I felt, since the poor beast was moving at such a trot that my pants were hiked up to my knees. I also remember the welcome you gave me, the good fire and the excellent meal I found waiting, and then my bed which dear old Aunt Amélie had warmed — a kind comfort that I had not experienced before, nor since. Then, when I rose in the morning and reached the landing that lead from the kitchen to the courtyard, I recall my surprise at seeing you, rifle in hand, as you watched for blackbirds by the four cherry trees near the church apse. The next day was your evening with old Bibard and the schoolmaster and cantor Father Charon. I was surprised to find myself face to face with such an unfortunate, deformed creature; that and so many other things were like a new life for me, but it would require too many pages to relate it all. I remember poor old Marie, Aunt Amelie, and you hovering over everything with a kindness that was both dignified and good-natured. I have not forgotten anything about these childhood impressions, and I think of them often.

This delightful, simple little village was in the midst of fresh and pleasant countryside and surrounded by calm horizons of low green hills. Sinuous, tranquil rivers of water that was always clear flowed through the local meadows and woods. In the months he spent here the young artist acquired a deep fondness for nature, and he has retained it. He indulged in long poetic reveries during which he gathered and stored away all of the intense feelings that arose as he contemplated the rural beauties before him — beauties which changed every day.

Even today Bouguereau remembers fondly how he used to stand and contemplate sunsets in the golden mist of the Gironde, and how his uncle would take him to visit the nearby churches and castles. These educational outings sparked his interest in the area, and prompted him to return during his holidays and make similar tours of that picturesque region. No professional archaeologist could give Bouguereau lessons about the origins and developments of civic and religious architecture in Aunis, Saintonge, Angoumois, and Poitou; no one knows their characteristic monuments better than he does.

☞ This book remained untranslated for more than a century. If you would like to help me bring other neglected titles to English readers, you can leave a tip with PayPal:

In the rectory’s modest library, the Lives of the Saints and the Bible were the young artist’s first books. He used to go off into the meadows, sit in the shade of a hedgerow, and revel in the idyllic stories of Rebekah, Ruth, and Boaz. He would read of shepherdesses who saved cities from the invaders, and miracles of roses blooming within the aprons of kind queens, and he dreamed of putting all these things into paintings on church walls.1

The good country priest, who had doubtless forgotten much of his own Latin in the exercise of his rural functions, soon sent his nephew to the college in Pons. The school was under the direction of an eminent priest named Boudinet, who later rose to become bishop of Amiens. Boudiner had transformed the school into a highly successful institution, with no less than three hundred pupils. Bouguereau received his first drawing lessons from a professor named Sage, who had studied under Ingres. A paternal aunt from La Rochelle piously collected and preserved the young artist’s first artistic efforts which, in their childlike naivety, show a wide range of ability: there are three-masted ships with fantastic hulls and sales, cathedrals out of a Piranesi, and landscapes with the most daring tones. In a note that accompanied these products of his artistic imagination, the young schoolboy is pleased to inform his aunt that he ranked eighth out of the thirty pupils in his class, and that he is digging into Latin with pleasure. And so it is here that he begins to learn about pagan antiquity. He is made to read mythology, fables, Ovid, and Virgil. It all enthrals and enchants him, opening up new regions of charm and poetry that he explores with tireless, ever-increasing curiosity.

The “roses blooming within the aprons of kind queens'“ is a reference to Saint Elizabeth of Portugal (1271–1336). Elizabeth of Aragon was devoted to caring the poor, but her piety was perceived as a reproach by some people at court; her husband King Dinis forbade her from leaving the castle to distribute alms. When she was caught leaving with an apron full of bread, the food miraculously transformed into roses.