I Am Determined to Do My Duty

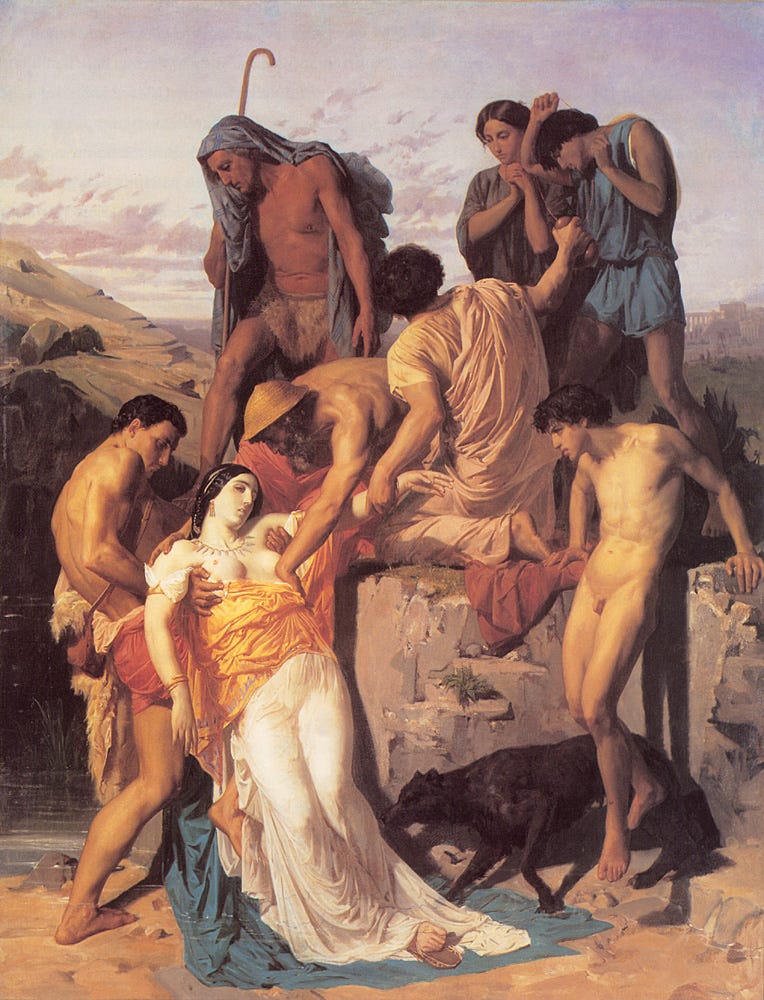

William Bouguereau's life as a soldier during the Siege of Paris

Marius Vachon’s biography of William Bouguereau was published in 1899 by Alexis Lahure (1849–1928), a printer with offices close by the Luxembourg Garden in Paris at 9, rue de Fleurus. As far as I know it is the sole contemporary account of the painter's life, which is why some remarks about and from the artist are in the present tense.

What follows is an excerpt from my translation (an uncorrected first draft). You can find previous instalments here.

There are seldom interesting, external events in the life of an artist who is absorbed in his work and lives only for his art and has no ambition but to advance in it and bear faithful witness through it. However, when an artist’s life has been punctuated by events as tragic and painful as the ones that marked Bouguereau’s youth and middle age, it is not unprofitable to show the role, more or less direct and active, that he was able to play in them. For his participation in these events had a marked effect on his ideas and his temperament, and a biographer should not neglect such important psychological influences.

In 1848 Bouguereau served in the National Guard and was involved in the events that took place in May and June. In his journal, he mentions May 15 with some emotion: “The drum beats and calls the citizens to arms. What has happened? That was the question one everyone’s lips. There are rumours that the Chamber of Deputies has been stormed. Hearing this, everyone rushes to obtain their weapons. Numerous columns form up and wait for orders. Everyone was making conjectures, assumptions about one thing or another, and so on. At last, the colonel goes past at full gallop. He looked unsettled, and seemed extremely agitated; his face displayed fury and rage. He had ammunition distributed and ordered us to march. The next time we saw him, his right arm was in a sling. We marched towards the National Assembly.”

In June, Bouguereau fought the insurgents alongside one of his studio mates, Isidore Pils, who had also enrolled in the National Guard spontaneously, saying that “art can not bloom in the midst of storms”.

The bloody events of 1848 instilled the young man’s soul with a profound aversion to politics and politicians. Bouguereau resolved to always keep himself apart from that world, and to never offer anything that might look like an affirmation, public or private, of opinions for or against any regime. He was not one of the Second Empire’s most faithful devotees, nor was he among its irreconcilable opponents. All his life, he has desired to be — and made it clear that he will remain — a simple citizen, one who ardently wishes for his country’s success and prosperity, and who supports order and peace in the streets and in the hearts of men, so that everyone can work and can enjoy the fruits of their labours.

When the Siege of Paris began in 1870, Bouguereau did as he had done in 1848 and joined the National Guard. He signed up even though he was exempt from military service due to both his age and his status as a former member of the French Academy in Rome. His battalion was commanded by Jules Bergeret, who would go on to become a military leader in the Paris Commune. The two Flourens brothers served with him.1

He did his duty, from beginning to end, with a patriotic attention to detail. He humbly accepted the simplest tasks and bore physical and mental suffering stoically; he was sustained by his vigorous temperament and by the ardent hope that Paris might be saved by widespread acts of heroism.

Bouguereau’s family had taken refuge in the city of La Rochelle. In the letters he was able to send them (by way of hot air balloons and messenger pigeons), the artist described the life he was leading with humour and philosophy. In some ways they are the painter’s diary of the siege, and I will quote from several interesting pages.

Right after Paris had been surrounded, he writes:

As for me, I am determined to do my duty. I will do it without boasting, and, I hope, without too much fear. My friends are as resolute as I am, which buoys our spirits. If the provincial towns can manage to assemble a force to relieve us, with a little effort on the part of those who are responsible for organizing the country, we may come through.

He began active service on 28 September and describes some of his duties:

I was on guard at the fortifications from Monday to Tuesday; I will not say that it is amusing, but it keeps me busy and, in this time when it is impossible to do intellectual work, it is something.

A few days later, he describes how he spends his time:

My life, as tumultuous as it may seem to be from afar, is actually very calm and very settled. Every morning I get up at six o’clock and we conduct drills from six ’till eight. Sometimes, there is fatigue duty, as there was today, for example. Then I distributed ammunition from ten o’clock to noon, and from five to seven I returned to the exercise yard. For the rest of the time, I go on walks, make a few visits, and so on. Every four or five days, we stand guard on the ramparts for 26 or 27 hours at a time, spending one night at our post or in the open air. I have already been on guard duty once; but, you know, I’m not very sensitive to cold, and do not really suffer from it.... As for doing any work [i.e., painting], that is out of the question. I’m in the National Guard, and that’s all there is to say.

One letter, dated 8 November, is full of patriotism. It shows the Parisian public’s state of mind, and their determination to hold out until the bitter end:

When you are far from your own family and have heard nothing from them in nearly two months, you are allowed to dream. Well, we have cherished the dream of departing as soon as the armistice is signed. We will go on foot, by carriage, on horseback, or by rail, and try to reach the people we love. Would it be possible to go on leave now, and return to Paris in time? This is another problem that needs to be solved; for no matter how much we want to make this journey to our families, there is nothing in the world that could convince me to leave Paris right now. If you knew the opinion people have of those who, out of fear or prudence, thought it best to move further out. Or the ones who, like Mr. X, did not even return…

Are things better in the country? I doubt it. Besides this stigma that attaches to anyone who does not do his duty, are those who flee really safe? Who can say to us that they will avoid being called up, in the same way they were able to avoid the troubles and dangers of the Siege? Until now, the dangers faced by the National Guard have been paltry: a head or chest cold, little fatigue sometimes. What does that amount to? There are other things to worry about.

The food is lean. No more butter, no more fat, no more cheese, no more milk; and 40 grams of beef per person per day. There is not any more coal either. Fortunately a comrade has set aside some provisions and I still have clarified butter, bacon, and ham, as well as potatoes, pulses, rice, and cheese — things which can now only be found in the best restaurants. Bread and wine are still freely available. This diet is not too difficult for me; beef is often replaced by horse meat, but it is also being rationed now. Apparently donkey is quite good to eat and can be had for somewhere between three and a half to four francs a pound. That will be something different to try.

☞ This newsletter is free to read. If you would like to support me as I translate neglected works into English, please ask your library to buy a copy of my latest book — check their web site and you will probably find a page where patrons can request a title.

The e-book edition on OverDrive is easy for institutions to order, so send them this link:

https://www.overdrive.com/media/11080225/prison-and-deportation

It will only take a moment of your time, but it would mean a great deal to me. Thank you!

Presumably Émile and Gustave Flourens