Misery and Indignity

Koch's comrade finds it hard to believe that he is a type designer

The German typographer Rudolf Koch (1876–1934) wrote a memoir about his experiences during the First War. I am translating it into English and posting a few excerpts as I go. You can find them all here.

In this instalment, Koch is relegated to painting road signs. When he points to one of his typefaces in the newspaper, a fellow soldier thinks he is putting on airs.

Tonight, once again, I am really tired of it all. On 18 November there was work duty to clear the road, and the whole squad had to shovel away the big mess of snow. It was cold and we had to stay outside through lunch. Towards the south there was a steep mountain range covered in fresh snow. In the middle of a meadow stood a lonely, sick horse with his head hanging low. He didn’t move all day and probably remained that way until he fell down and died of hunger and exhaustion. I have often seen such poor, abandoned animals in Serbia. We marched back at 4 pm. The road was blocked up and we were overtaken by a long column of prisoners. It was a familiar sight, although the indescribable misery of these sick, weak, half-starved people never ceases to move us. Women were peering anxiously into the ranks of men. Suddenly a young woman cried out and rushed towards one of them, who immediately fell into her arms. They only managed to exchange a few hurried words, and then the German cavalryman who was bringing up the rear rode up and struck him on the head with his lance; the prisoner quickly returned to the column and, without looking back, trudged away from his home and his wife.

On 19 November I was ordered to go and to work as a painter, specifically to make road signs in German. We were in a carpenter’s shop and it was quite comfortable, all very dry and warm. There was not much to do, and for the most part we sat on a workbench and chatted. I struck up a conversation with the young soldier who was next to me; he was the son of a book printer. We talked about a number of things, and I asked him if he knew any of the newer typefaces. He replied eagerly and confidently that he did. There was a newspaper on the table that used my typeface, and I asked him if he was familiar with it. He didn’t know the name straight away; I said it was Kochschrift and that I had designed it.1 He looked at me incredulously and thought that I might have set the type, but when I explained that I had created it and that my name was Koch, he shook his head and explained that he couldn’t believe it since, as far as he knew, only professors designed those kinds of things. I kept silent, embarrassed, and on the way home I had to think seriously about whether I really had made the typeface. That was my only moment of triumph as a type designer, and it fell miserably flat.

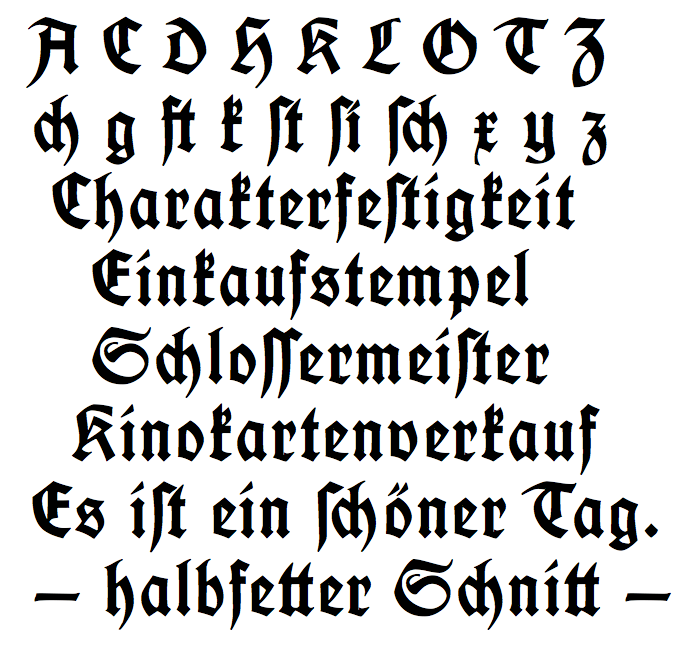

I believe Koch was referring to the Deutsche Schrift he designed while at the Klingspor Type Foundry, pictured above in a revival issued by Delbanco Frakturschriften.