Prison and Deportation, #04

Msgr. Gabriel Piguet's Memoir

This is the fourth instalment of my translation of Msgr. Gabriel Piguet’s memoir Prison and Deportation. If you would like to read the rest of the book, you can order a copy here. You will find other excerpts here.

Chapter 6

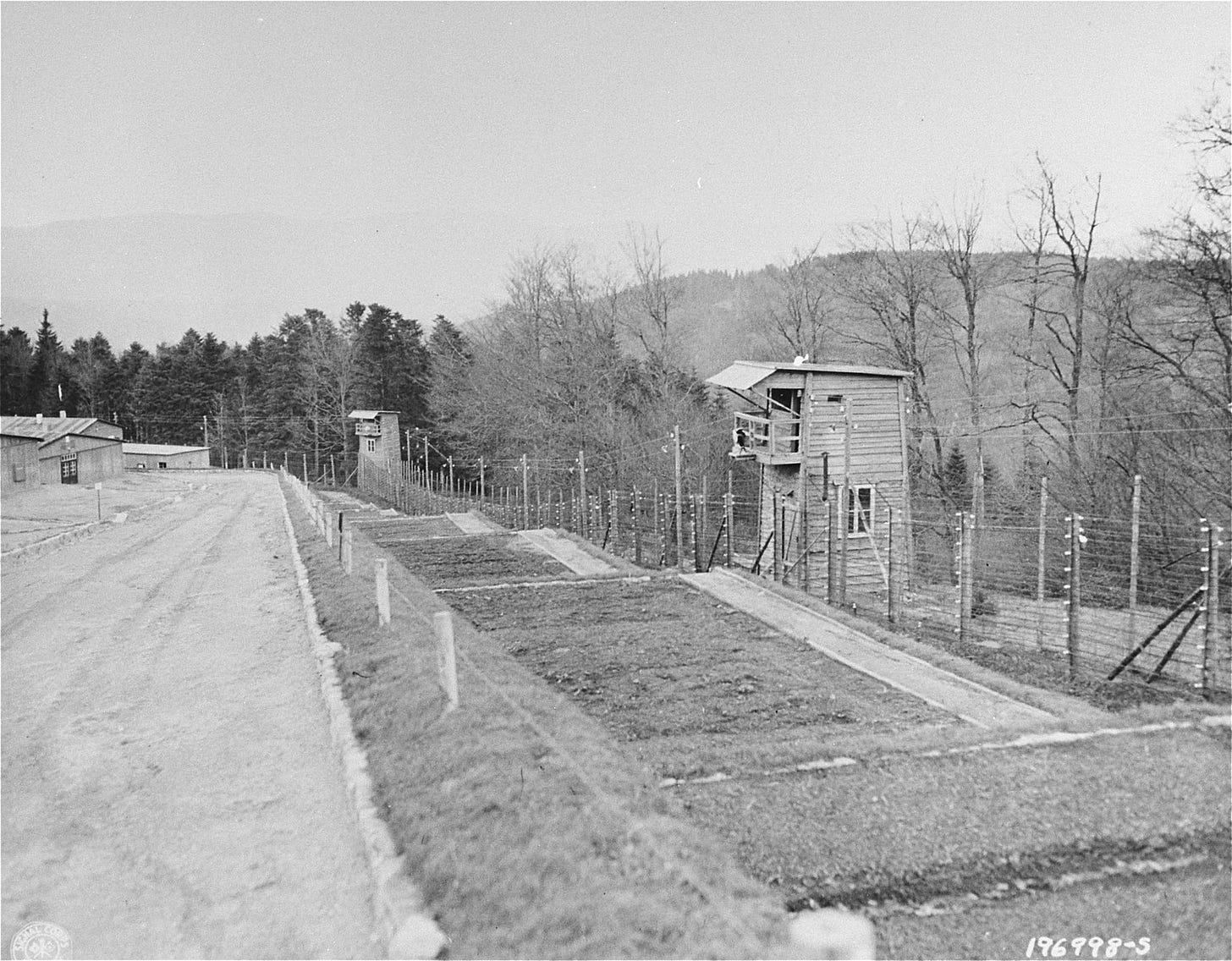

Natzweiler: My First Concentration Camp

On the morning of Wednesday 30 August, after a journey of ten days and ten nights, the train from Clermont-Ferrand arrived at the small Alsatian station of Rothau. Prisoners soon appeared, dressed in uniforms with blue and white stripes, and wearing hats in same colours and style.

My companion, who was as astonished as I was by this strange attire, said to me: “I hope that we will not be dressed like those men.” I shared this hope. What's more, at that time I still could not imagine that a bishop who had been imprisoned without a trial could be put to work in a labour camp, never mind mixed in with common criminals. Despite everything we knew about Nazism, our minds had not yet grown accustomed to the thought that a cruel and partisan police force had the power to inflict punishment outside of any court of law.

It did not take long for the idea to set in.

All the prisoners got off the train. The head of the Werhmacht detachment, knowing that it was difficult for me to carry heavy luggage because of a wound I had received during the First War, had them taken to the road where a detachment of SS soldiers was waiting to relieve the Wehrmacht soldiers from Clermont prison.1

Now here we were with new guards, SS men. They lined us up. The men who had my luggage gave it back to me. It was the beginning of a new life, and it was a brutal start. I was kicked in the kidneys while one of the guards violently beat the Prince of Bourbon with his rifle. My fellow prisoners rushed over to help me carry my heavy suitcases.

The procession set off. The houses of Rothau had their shutters closed. Who knows, were there eyes behind the shutters who watched these new prisoners pass by? The procession consisted of our entire group from Clermont-Ferrand, and also included others from the prison in Nancy. There must have been between four and five hundred prisoners in total. The road was uphill. Despite the fact that some of us were of advanced age, we were forced to quick march up this steep hill for eight or nine kilometres as if we were alpine infantry. My cassock, my episcopal insignia, my pectoral cross and my ring had already singled me out for attention by the vicious guards. I was rudely insulted over and over again, so much so that some of the French who understood German translated these ignominies for their comrades; they wanted to know what kind of insolent things were being said so loudly, and with such aggressive hostility.

Insults were not enough for these young men, so they loaded me down with my own suitcases as well as those of others who were behind me. I was hit several more times, but above all it was the terrible weight that was more than I could bear. After the arduous journey, the weakening effects of three months in prison, and, it has to be said, the weight and shape of an ecclesiastical costume that was ill-suited to this kind of exercise, it was all too much for me. A doctor who was a prisoner and part of the column later said to me: “When I saw you on the side of the road at Rothau, I thought: If this bishop has a heart condition, he won't make it to the camp.” I did not have a heart condition, but neither was I baggage handler who had been practising weight lifting and climbing.

I collapsed on the path about a kilometre away from the camp, overcome by extreme fatigue. Thinking that I was in danger of being shot by these odious guards, I put my soul in God's hands... Instead of ordering that I be killed, the guards told two of my comrades on this climb to Calvary to help me up and see that I made to the camp.

As I passed under the camp gate, a hand took off my ecclesiastical hat and put it on backwards. I put it back on without turning round to see what obviously witless person had played this wretched joke. The hand immediately repeated its trick and I continued on my way without looking back, holding my hat in my hand.

The Natzweiler camp faced due north and was situated amidst mountains that bristled with fir trees. It was laid out in such a way that the barracks were stacked one on top of the other and required constant ascents and descents to get around. Everything had been carefully designed and constructed to make one's stay a painful one.

I did not have to wait long to learn about the atrocious life in the camp and the rigours of its long winter. The bell had been rung, and on all sides we saw prisoners rush in from near and far to try to make contact, if they could, with the new arrivals.

We stopped at the bottom of the camp. Many of my fellow inmates from Clermont prison and our famous train approached me. I was touched by their sympathy. I was fortunate to have some food in my bag, and I was able to share some of it with these men, many of whom were my faithful friends from the diocese, and our common ordeal had made us brothers in suffering.

An icy wind swept across the top of the mountain. We were quite warm on the way up, but we soon grew cold again...

Our names were called alphabetically. On this open-air site, we were relieved of all our luggage, all of our clothes, the contents of our suitcases, our food supplies, and our so-called valuables such as watches, money, and wallets. My pectoral cross and my episcopal ring were also taken from me. A priest who worked as a nurse, Abbé Jean Quichot, tried to rescue a beautiful rosary that I gave to him for safekeeping. A savage yell from an non-commissioned SS soldier forced the kind abbé to relinquish the rosary, which I then had to hand over the camp administration along with everything else I owned.

Prayer books and religious objects were banned at Natzweiler, as they were in all concentration camps. “There is no God here,” said one of the guards to a prisoner. In fact, any outward act of religion was forbidden. I later came to know General Delestraint quite well, and when he arrived at Natzweiler and complained about the way they were treating a French general, the SS replied: “There are no generals here. Here you are a number. Here you enter through the door and leave through the crematorium oven.” A grim prediction!

My admission ended with a shower and the provision of striped trousers. Since there were insufficient supplies, I was given a colourful civilian jacket with the large letters KL (short for Konzentrationslager) painted on the back. I wore ill-fitting wooden sandals on my bare feet.

This uniform and the process I underwent made me realise the full extent of my new situation and its tragic horror. The inhuman cries of the guards, the huge dogs trained on the prisoners, the camp's sinister appearance, the atrocities that the veteran prisoners recounted to the new arrivals, the loss of everything (including one's most personal and necessary objects) made me realise that I had fallen into the most wretched of human conditions. I joined myself to God. I could feel that He was everywhere, whatever the SS might claim, and that this hellish setting could neither darken nor alter His divine and comforting presence, which was the only support in such misfortune.

A red triangle on my jacket, which was the insignia of a political prisoner, and a number completed my uniform. Officially, that was all I was now: a number. But not to my fellow prisoners. Many of them came to greet me on that first evening in prison, and to the end I enjoyed the respect, sympathy, and friendship of my fellow deportees.

This tragic entry into the camp, preceded by all the other incidents, had left me physically exhausted. At the evening roll call, I could no longer stand on my own two feet. I would have fallen over if it had not been for the men next to me, who very charitably helped me to stand upright. My first night in the overcrowded barracks was a feverish one. I was able to avoid sleeping among unknown Russians, with whom I had initially been placed. In the end I was put between two Frenchmen, one from Alsace, the other a man from the south of France who had arrived in the convoy from Clermont-Ferrand. When I awoke the next morning at 4.30am, I was as tired I had been the day before. Holding roll call in the rain did not help. But Providence watched over me. I was taken for a medical exam and nearly had to be carried there by my comrade; I was admitted to the Revier by a Norwegian doctor. The Revier was the infirmary, and I would only be allowed to remain there for six days. A wave of hope swept over us with the sound of American cannon fire, but it resulted in an order for the general evacuation of the camp.

Natzweiler was for me neither a residence nor a tomb — as it was for so many others, alas! During those days and nights in the infirmary, the crematorium burned non-stop. Large numbers of men and women were taken there. Where did they come from? What had they been charged with? In my bunk, where I remained without a specific illness but completely exhausted from excessive fatigue, I could not see the flames and smoke of the crematorium, but I was able to hear my bedfellows, attentive to these macabre executions, who told me about the increased activity of this dreaded oven, whose terrifying glow they observed.

I only spent a few hours in the first section of the infirmary, where I was visited by the camp commander, who ordered General Delestraint, an American major, an English lieutenant, the French bishop, and a few other men, including a German and two Luxembourgers, to be brought together in the same room. Is this a privilege? Once again, they employed the hot-and-cold method; at first there was apparently kind treatment, then harsh punishment. When we left the infirmary, the Prince of Bourbon and I were told that we had to wear a red dot on the back of our clothes, a symbol usually reserved for prisoners who had attempted to escape. This was a completely unjustified measure, even in terms of the concentration camp regulations, and it was a dangerous mark that justified in advance any attack on a Prince and a deported bishop. There was even worse in store, as we were to learn later.

The police had created a file for each prisoner and these police files accompanied us to Dachau, where we were to be transferred a few days later. The one for the Prince of Bourbon and myself looked like this:

Sonderhäftlinge (III)2

Bourbon Xavier ......................... (with dates and

Piguet Gabriel ........................... places of birth)

It would seem that, in police language, this wording and the three Roman numerals meant that these two detainees were exceptional prisoners and should be sent to a special camp. When the convoy arrived at Dachau, this note fell into the hands of prisoners who had been detailed to serve as secretaries; they were priests. They realised that this kind of note amounted to a death sentence and removed the compromising piece of paper. During the winter of 1944, I later learned from a Belgian secretary that they had scrubbed our files so thoroughly that they contained no trace of such information. The police at Dachau never knew that the original document existed.

I only learned that the files had been switched at the end of my captivity. At first I hesitated to believe it, whereas the Prince of Bourbon knew about it earlier and believed it to be true.

Today I know that it is an indisputable fact. The proof is that the original of this form was not only removed but kept and is now in Paris. Several French and Luxembourg priests are aware of this affair and Abbé Jost, a former deportee and chaplain general of the Luxembourg forces, retained a copy of the original. Those under God's care are well protected, and was not beyond His divine power to save victims from certain death in the criminal hell of the Nazis, where they were sent without trial, and without any possible defence.

There is no freedom in a world where there are concentration camps and police forces like this.

But let us return to my days in the infirmary at Natzweiler, where I came to know a number of French people and foreigners. I became acutely aware of all that the concentration camp represented and its tragic aspects — not only the part played by the Nazi commanders but also the behaviour of certain prisoners who were common criminals or had ties to questionable groups that were capable of the worst acts. No one apart from the deportees can understand all the mysteries of a concentration camp, and only eternity will shine a full light and give us the whole truth. There are some very base people in the world... The concentration camp did bring about magnificent spiritual ascents, and it allowed the religious faith and patriotism of some very good souls to shine forth. But it also provided loathsome beings with all kinds of despicable means to perpetrate evil through their wickedness, treachery, threats, and crime.

We knew or guessed who the spies, traitors, and executioners were — later, many of them paid for their vile acts with their lives. This miserable page in the history of the concentration camps has a magnificent counterpart in the almost unanimously good camaraderie, the strong friendships that were formed in the community of suffering, and the fraternal and even devoted affection felt between men who espoused different doctrines and opinions. The fellow feeling and the mutual, cordial sympathy that existed in the concentration camps should be remembered; it is a light and an example to follow in resolving the many difficulties we face in the arduous task of rebuilding the modern world.

This book remained untranslated for 75 years. If you’d like to help me bring other neglected titles to English readers, you can leave a tip with PayPal:

Msgr. Piguet served as a stretcher-bearer during the First World War and was seriously wounded in 1915. The bullet that struck him remained lodged in his spine for the rest of his life.

Sonderhäftlinge were “special prisoners”.