When Ginger Rogers Was the Sweetheart of Cape Scott

Memories of RCAF Radio Detachment No. 10, by Fred Farr

Something a little different in this post, with an account of life at RCAF Radio Detachment No. 10 — a secret, early-warning radar base that was set up on the north-west tip of Vancouver Island during the Second World War. It was written by the late Fred C. Farr.

I’ll return to my translation of Rudolf Koch’s memoir next week.

Many wartime memories must have been stirred by events marking this past Year of the Veteran.1 My own are of the RCAF’s radar detachment at Cape Scott, that tip of land tilted slightly to the west at the northern end of Vancouver Island. Following Pearl Harbour, the defence of Canada’s west coast became a priority, and Cape Scott was chosen as the site for one of a chain of radar detection stations stretching from Victoria to the Alaska border. By the time I arrived in February of 1943, construction was complete and the station was fully operational.

Vital to its survival were craft such as the Mermaid and Combat, 60-foot fishing boats that had been commandeered for the duration to serve as supply ships. They had crews of about ten, all with Air Force rank so that a deckhand might have the incongruous title of Leading Aircraftman. Their home base was Port Hardy, the most northerly port of call on the island for the commercial passenger and cargo vessels that plied the inner channel. The voyage from there to Cape Scott was a hazardous one and could be made only under certain wind and water conditions. If unfavourable weather conditions held for several days, men at the Cape would go on emergency rations, and sometimes mail, fresh meat and tinned milk were dropped by plane. Men on their way to a posting there would be held at Port Hardy or at an RCAF seaplane base at Coal Harbour, some ten miles south, until weather was deemed suitable to attempt the trip.

There were two parts to the station at Cape Scott: the operations site and the camp-site. At the former, the radar equipment for detection of enemy aircraft and the tracking of our own planes stood atop a headland at the very tip of the cape, while at the latter, sleeping quarters, orderly room, mess hall, canteen, sick bay and the other buildings with more domestic uses occupied much lower ground some distance away. Some of these structures stood in a bog, and wooden catwalks connected one with another. A makeshift road consisting mostly of two plank tracks connected camp and operations and enabled the station transport truck to travel between the two. Along the way there was Cape Scott Sand Neck, a bridge of sand that actually joins the Cape to the island, and often after a high wind we had to dig out the plank tracks before the truck could proceed.

Except during the very worst windstorms when the revolving aerial was locked fast in one position, we were “on the air” around the clock, and the radar “mechs” and operators had to work in shifts at the operations site. In addition, we all took turns on wood-cutting detail. The original plan had been to supply the detachment with coal for heating and cooking, but getting it there was difficult and driftwood was so abundant on the beaches that burning wood seemed more sensible, even to the military mind.

Also, whenever the supply boat visited — which was about every other day, weather permitting — everyone who was off duty swarmed down to the beach to help with the unloading: “organized sports” it was called. There was no wharf or float and no shelter from the heavy seas. The supply ship used to anchor off shore and lower its dinghy, while a rowboat from the Cape detachment set out from shore; both small boats then went back and forth between supply ship and beach until the incoming cargo was all on shore. Usually the mail bag came ashore first; the corporal clerk would take it to the orderly room and have letters and parcels from home all sorted and ready for distribution by the time the “organized sports” were over. (Some years later one of the corporal clerk’s daughters turned up in a Grade 10 class I taught, confirming that the whole experience had not been a dream.)

Then came the sides of beef, sacks of potatoes, cartons of canned goods, pieces of technical equipment, hardware, housekeeping and medical supplies. And there were barrels of oil, always barrels of oil. Oil was our life blood, since it was required to fuel the diesel engines that powered the generators that provided the electricity that ran the equipment that was our reason for being there. The barrels were tossed over the side of the vessel and then they were shepherded to shore by dinghy and rowboat and, closer to the beach, by our guys in wet suits or swimming trunks, depending on the weather. I was not at the Cape when the 1500 pound safe was delivered by the Combat, but the saga of its being unloaded and brought ashore in the dingy became one of the legends of the west coast detachments. And no easier than the safe to bring ashore was a piano for the canteen which, as it turned out, no one could play.

Other, unscheduled, events required everyone to pitch in on his off-duty hours. For example, in late summer of the year that I was there the B. C. Star, sister ship of the Mermaid and Combat, disappeared with all hands while headed for a detachment in the Queen Charlottes. We were requested to trace on foot the shoreline of the Cape as far as possible in both directions to search for wreckage that may have washed ashore. Nothing was found.

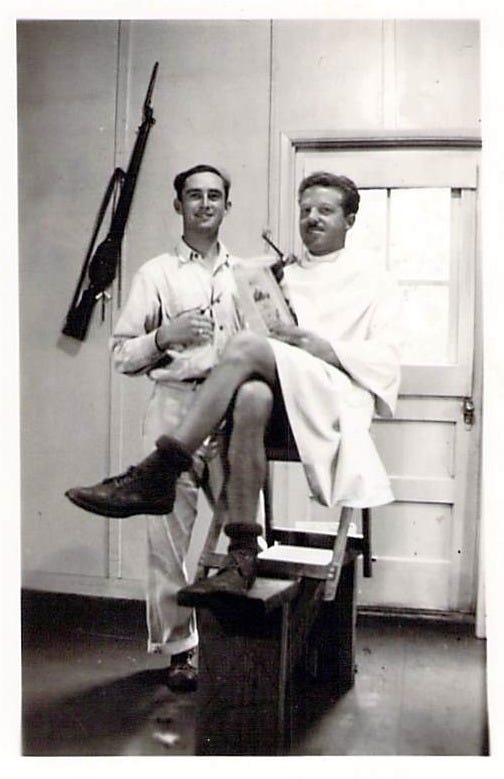

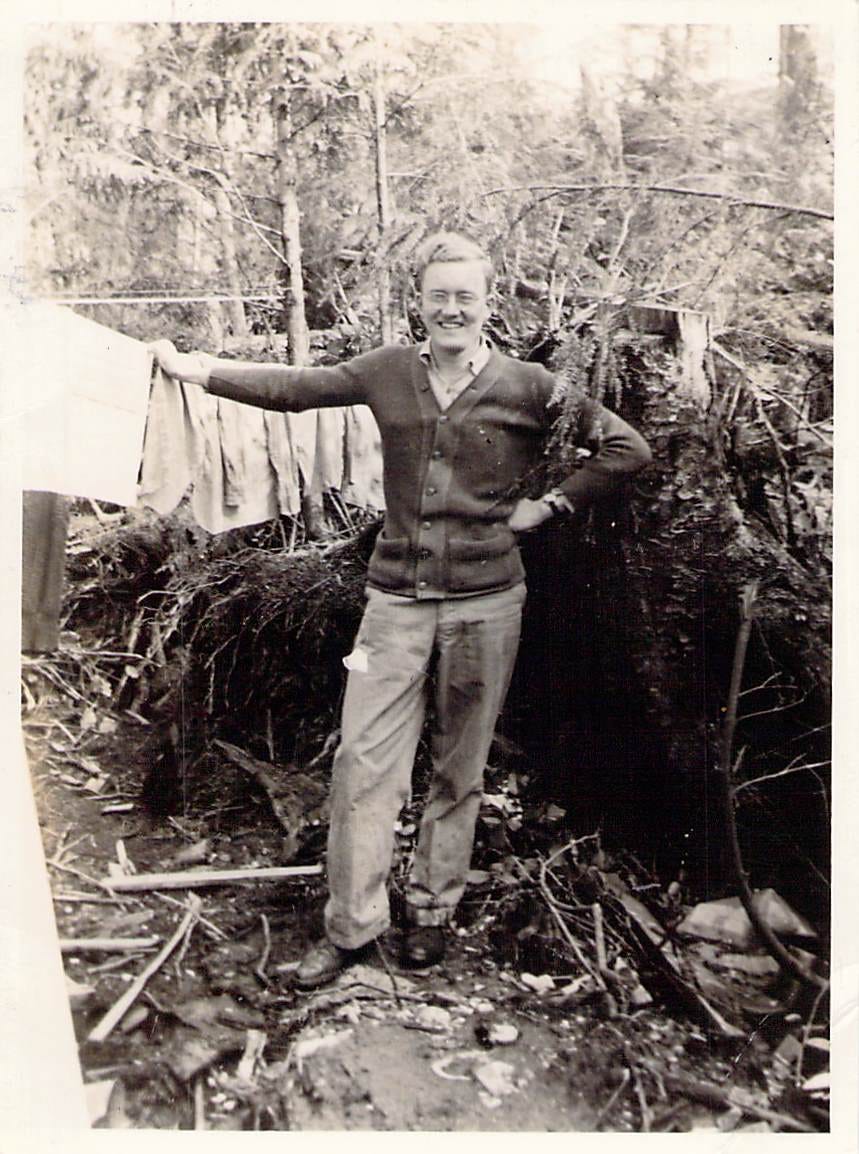

One might think that without such off-duty emergencies and in such a place that boredom would set in. But such was not the case. We did our washing, played ping pong, listened to records, played cards, wrote letters, read, and shot the breeze. Two radar operators went into business and for a price did the laundry for those guys who, even in these circumstances, could not bring themselves to do their own. The process involved not only washing the various items of apparel, but firing up the woodstove to heat the water used. One radar mechanic in his off-duty hours became a barber. We started a mimeographed weekly called The Isolationist, and we produced a talent night.

The supply boat usually brought a movie that was shown each evening until a replacement arrived on the next boat. While I was there, we happened to get a run of movies with Ginger Rogers, one of the oldies that she had made with Fred Astaire and a number of the more recent ones that she made without him. The corporal clerk wrote her a letter on our behalf telling her that she had been named the Sweetheart of Cape Scott. In return we received a number of glossy publicity stills that we tacked up on the orderly room walls. The photographs were accompanied by a signed note so badly typed that we figured all the competent studio stenographers in Hollywood had gone into aircraft plants and Ginger had typed it herself.

The canteen where the films were shown was, of course, the most popular building at the camp-site. It was the scene of endless table tennis tournaments and of heroic drinking parties every night after the supply ship had brought a new supply of beer. One night in September, 1943 there was free beer for all to celebrate Italy’s surrender to the Allies and, for those who didn’t drink, the equivalent value in chocolate bars. Occasionally a padre was dropped off, and for the service which he conducted a makeshift altar would be draped with fresh cedar boughs and topped off with a driftwood cross.

Most of these activities could be carried out on the many days when rain came down in sheets for hours at a time. The rain seemed to remind us just how the forest that surrounded us came to be so dense and lush and green and why one day it would reclaim our settlement and cover our every trace. But on those days when the sun shone, we explored the nine sandy beaches and countless rocky coves. We played volley ball on the sand and hunted for shells and strange driftwood shapes from which we made lamp bases. We lay in the sun and tried to articulate our feelings about the place and why we were there. I don’t suppose the words pollution or environment ever passed our lips, but I think we realized that we were in a rather special place. We speculated about the future of the Cape; we wondered whether we were the last to see those beaches stretching empty and unspoiled for miles before post-war development would turn them over to the tourist and lumbering industries.

Fortunately, we were not. In 1973 Cape Scott Provincial Park was established, and that wilderness, never quite tamed by us, would remain as it was for others to enjoy. It is accessible only by trails, and the trailhead is reached only by a logging road from Port Hardy; now a thriving community of 5000 and the northern terminus of the Island Highway down to Victoria. The intrepid hikers in the park are given various warnings in the park brochures: “the park is a wilderness area without supplies or equipment of any kind”; “torrential rains can be expected at any time and may last for days on end”; however, “the visual and emotional rewards, especially on a clear day, are beyond compare.” We knew all about the torrential rains that lasted for days on end, and we also had those visual and emotional rewards.

Some years ago I wrote to the B.C. government to ask whether there was any kind of memorial in the park to commemorate the RCAF years at Cape Scott. A reply from Premier Vander Zalm himself said that there was no knowledge of such a memorial to the RCAF in Cape Scott Provincial Park.

I am glad that the B.C. government has done what it could to preserve the natural beauty of Cape Scott, and one hopes that the hardy visitors to the park will continue to see those silver sands as we saw them those many years ago and not stained with globs of bunker fuel and strewn with the carcasses of strangulated birds after another Exxon Valdez. But it would also be gratifying if somewhere along the trail they might come across a discreetly placed plaque commemorating us and the time when we were there, when Ginger Rogers was Sweetheart of the Cape.

After the war Fred Farr studied English language and literature at Victoria College, University of Toronto, graduating in 1949. He became a teacher and spent most of his career at Downsview Collegiate.

Fred was on a distant branch of the family tree (the husband of my first cousin, once removed), but to me he was a close, avuncular friend. He died on this day in 2012.

He asked me to type up this account of his time at Cape Scott for publication — I can’t remember if we sent it to the Grope and Flail or the University of Toronto alumni magazine. In any case, it wasn’t printed. I found it while cleaning some digital clutter, and decided to post it on Substack; perhaps the relatives of other men who served at Cape Scott will find it.

The Canadian federal government declared 2005 to be the Year of the Veteran.

Thank you for sharing this.