Pierre Jean Van der Ouderaa and a Plea for Posterity

Émiel van Heurck wrote the artist's obituary, and I have translated it.

A few days ago George Bothamley wrote a post about the Belgian painter Pierre Jean Van der Ouderaa (1841–1915), and suggested that the artist deserves more recognition.

I agree, which is why I have translated the obituary that Émiel van Heurck wrote for the Royal Academy of Archaeology of Belgium in 1919.1 You will find it below. As far as I can tell, it is the most complete account of Van der Ouderaa’s career; there is no entry for him in Wolfgang Freitag’s Art Books bibliography, nor could I find any digitized monographs on Archive.org, Gallica, or the Royal Library of Belgium.

Reading the obituary, my first reaction was to think what a pity it is that a hostile critic wrote the only enduring record of this artist’s life. We might have had a diary to tell us more about what happened in the Holy Land to prompt Van der Ouderaa to devote himself to religious art or, failing that, perhaps a brief memoir by a sympathetic friend. Still, even a hostile critic is better than nothing — better than oblivion. And I fear that oblivion is precisely where all but the most famous (or infamous) artists of today are headed.

I hope I am wrong, but my impression is that a great many people have abandoned long-form writing in favour of the brief and the ephemeral. Terse snark has triumphed over substance. Will future generations be able to flip through the collected correspondence of their favourite painter? What kind of primary source material will fuel the biographies of the next century? Is it unreasonable to expect a contemporary artist to produce something comparable to Eugène Delacroix’s journal? It is poor form to answer one’s own rhetorical questions, but you get my drift.

So I am prefacing this translation with a plea for posterity. If you are an artist or literary type, please keep a voluminous diary and please write, print, and distribute essays about the interesting people around you. Leave your family and friends with something more substantial than a string of off-hand comments on Twitter.

Obituary of Pierre Van der Ouderaa

The artist Pierre Van der Ouderaa died in Antwerp on 5 January 1915 at the age of 73; he came down with a cold when the city was evacuated in October 1914. Initially he focused on historical painting but, following a trip to the Holy Land, he devoted himself almost exclusively to religious works. We also have several good portraits that he painted, including those of fellow artists David Col (now at the Antwerp Museum) and Constant Cap, as well as a portrait of the politician Paul Segers, and a self-portrait that the painter presented to the Musée des Académiciens in Antwerp.

Pierre Van der Ouderaa was born in Antwerp on 13 January 1841 to Dutch parents. His father was from Bergen-op-Zoom and his mother was from Roosendaal; they were middle-class people, and were already living in Antwerp when Belgium became independent.

After an initial period of study that was not particularly brilliant, our late confrère entered the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts at age 15 and was taught by J. Jacobs, Van Lerius, and N. De Keyser. He entered the Belgian Prix de Rome competition in 1865 and, in the initial round, he came first along with André Hennebicq. In the final round there was some disagreement among the members of the jury and Van der Ouderaa was only awarded second place, but this still provided him with enough funding from the government and the city of Antwerp to allow him to travel for three years. The painter left for Italy in July 1866. The next year, he and Albert Cogels went to visit Alger, Tunis, Oran, and Spain. In Rome, where he stayed for 18 months, he dedicated himself to making a serious study of human anatomy. He returned to Belgium in 1869 and on 5 July he married his cousin Miss Jeanne Van der Ouderaa, who was from Bergen-op-Zoom; he had taken advantage of his stay in Rome to obtain a dispensation to do so from the pope. When he came back to Antwerp he painted romantic fantasies, and then made a gradual change and began to produce large dramatic compositions that were usually based on the history of his native city. They established his reputation.

These works include Tanchelm Preaching (1870), Philippe van Artevelde Proclaimed Ruwaart of Flanders (1875), which was purchased by the Antwerp Museum but was later replaced by the Legal Reconciliation in the Saint Joseph Chapel of the Antwerp Cathedral (1879), Egmont's Widow Presented to the Magistrate of Antwerp (1876), The Official Reception of Charles V in the Garden of the Vielle Arbalète (1876), The Distribution of Roses (1877), Marguerite Harstein or On the Way to the Ordeal (1880), Legal Reparation (1883), The Joyful Arrival of Anne of Austria (1886), the tryptic of Jean Berchmans' Body on Display (1890) which was a gift of the Lagrelle family to the Antwerp Cathedral, as well as The Penalty for Perjury (1887) and None May Be Removed From His Natural Judge (1898), which hang in the criminal courts at Antwerp's Palais de Justice. We know that it was on the recommendation of Théophile Smekens, the honorary president of the Antwerp Tribunal and honorary member of our Academy, that the criminal courts were decorated with large compositions. Our late confrère Mr. Pierre Génard, the eminent archivist of Antwerp, provided the artist with the historical and archeological details that he required to execute a great many of his paintings, several of which were later popularlized by engravings.2

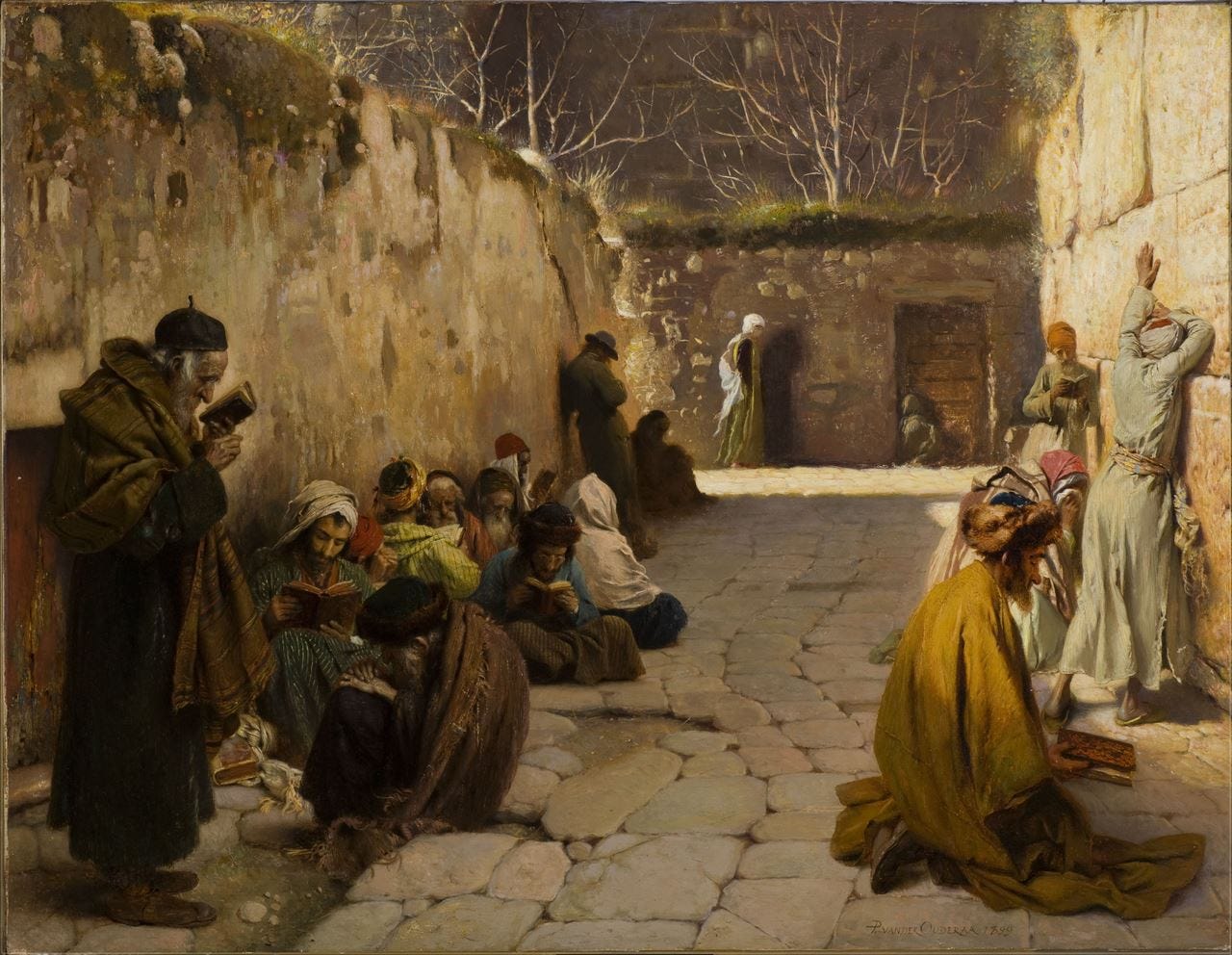

After being influenced by a trip to Egypt and Palestine in 1893, Van der Ouderaa devoted himself almost exclusively to the painting of religious subjects. These include The Massacre of the Innocents (1896), The Return from Calvary (1905) in the Antwerp Museum, Consummatum est (1909), Mother of Sorrows (1909), Mary Magdalene Touched by Divine Grace (1909), For Humanity's Sake (1910), The Holy Family (1911), and lastly Saint Francis at the Beginning of his Vocation (1913) — the artist travelled to Assisi at the age of 70 to complete this painting, and it was was his final large work.3

Van der Ouderaa's works are owned by museums in Antwerp, Brussels (The Last Refuge), and Dendermonde (A Legal Reparation). He won a number of gold medals, including one in Antwerp in 1879 for The Legal Reconciliation, one in Amsterdam in 1883 for Marguerite Harstein, and another in Berlin in 1896 for The Massacre of the Innocents. In Antwerp he was awarded the first place medal in 1894 and the second place medal in 1885, as well as a second place medal in Bordeaux in 1895, and silver medals in both Sydenham and Lyon in 1874.

Appointed a knight of The Order of Leopold in 1881, he was elevated to the officer class ten years later. He was a full member of the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts, where he had served as a professor since 1886. When Nicaise De Keyser died, they offered to make Van der Ouderaa the director of the Academy, but he declined in favour of Charles Verlat. When Verlat died, the post that should have been Van der Ouderaa's was given to Albrecht de Vriendt; I am told that this was the greatest disappointment of Van der Ouderaa’s life. In 1872, he received an offer to become head of the Academy of Prague but he refused on the grounds that he did not wish to leave his native city. The fresco painter Jean Swerts later accepted this position.

Van der Ouderaa became a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of Archaeology in 1891, and a full member in 1904.

While he was painting, Van der Ouderaa also engaged in literary studies that were in line with his interests. He contributed to various publications and even gave several presentations on the fine arts and about the trips he had taken.

Our confrère leaves two children: his son Norbert Van der Ouderaa, who is an ophthalmologist, and his daugher Mrs. Théo van Dormaal, who has had considerable success as a painter of flowers.

Van der Ouderaa was often celebrated by the public, but was he a great artist? I do not believe so. He was certainly a talented, conscientious, and honest painter — and he was, in every sense of of the word, a respectable man. An academic painter and an intractable traditionalist, he remained distant from and opposed to the great, renewing influences of modern art. His scholarly, precise, and frigid painting is largely unable to evoke a past whose spirit he did not comprehend. His religious pictures in particular clearly demonstrate that he is not to be numbered among the masters who have made our Flemish school of painting famous. While many of his works are impressive because of the brilliance of their colouring and the perfection of their design, one looks in vain for religious feeling in the works of this perfect Christian. I therefore believe that artist made a grave error by devoting himself to a genre that demanded a genius he did not possess. However, his memory will not perish, and his name will go down in the history of Flemish painting.

— Émiel van Heurck, 1919

If you enjoyed this post, subscribe below to receive similar translations by e-mail every week.

If you don’t want to clog up your inbox, you can also follow along via RSS.

Émile van Heurck, “Notice nécrologique,” Bulletin de l'Académie royale d'archéologie de Belgique, no 1, 1919, pp. 34-37.

I have translated the titles of Van der Ouderaa’s paintings into English. See the link to the Bulletin in the footnote above for the original French names. Lord knows how many of them were lost or looted during the two world wars.

I was not able to find a painting of St. Francis with precisely this title, but I wonder if it might be the one sold by Heritage Auctions on 7 June, 2019; the date is just one year off.

Thank you for this piece and I agree with your larger theme. How fascinating to hear directly from any historical figures in the midst of trying to navigate life and what a gift to us that so much history is left to us in 1st and 2nd hand accounts. I agree future historians, or curious amateurs (like myself) would be impoverished by the paucity and perhaps also the lack of quality in diaries, journals and letters.

These pictures are fascinating, striking at first glance and filled with detail that merits looking closely, and more closely. The obituary is so odd. Was the writer of the obituary trying to curry favor, or get himself out of trouble, by writing such a weirdly damning piece? The image of Francis with the birds, and the mourning women are filled with great feeling, it seems to me, although I admit they are lacking in that saccharine rolling one’s eyes to the heavens image of piety that other religious paintings of the period are often filled with. Is that what the author of the obituary is complaining about, I wonder?