William Bouguereau, #03

The painter kept a journal while he was a student in Paris. What became of it?

Marius Vachon’s biography of William Bouguereau was published in 1899 by Alexis Lahure (1849–1928), a printer with offices close by the Luxembourg Garden in Paris at 9, rue de Fleurus. As far as I know it is the sole contemporary account of the painter's life, which is why some remarks about and from the artist are in the present tense.

What follows is an excerpt from my translation (an uncorrected first draft). You can find previous instalments here.

First Years in Paris

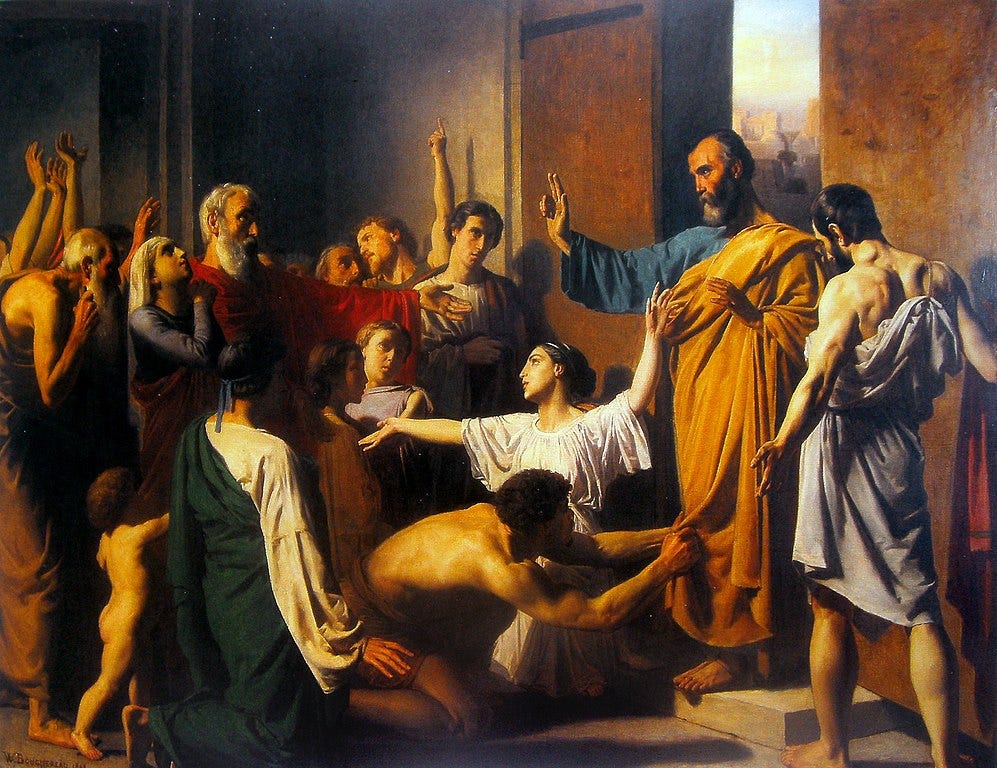

In those days, Picot’s studio was famous in the artistic world.1 On the advice of the director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux, Bouguereau enrolled there immediately. According to Isodore Pils, who was one of Picot’s most illustrious pupils, the painting-master’s “works and lessons all bear the stamp of the highest tradition — he was one of those who sacrificed everything to preserve the sacred customs of old and transmit them intact to their successors.” Among others, Bouguereau's fellow students included Lenepveu, Cabanel, Henner, and Gustave Moreau. The young artist’s life during those initial years of Paris should serve as an example of energy, courage, and willpower to future generations. His only financial resources were the meagre sums he received from his family, about twenty sous a day. His typical menu consisted of a piece of bread, a piece of cheese, washed down with clear water.

He often did not have enough to eat. Recalling those impoverished years, Bouguereau said to me: “But it did not matter very much to me; I did not even think about it. Whether I ate or did not eat, no matter. I had no other concern besides drawing or painting.” He was first to arrive at the studio in the morning and the last to leave in the evening, and he never wasted a minute. Afterward his classes he used to go to study perspective, natural history, and anatomy. He lived alone; he was never seen in dens of pleasure, nor in any of the fashionable artistic or literary cabarets that were frequented by young artists and writers at the time. He was not a member of the noisy and jubilant artist colonies in Bougival, Marlotte, or Barbizon either. Bouguereau’s period of study at the Picot’s studio, however, did not last long.

On 8 April, 1846, he was admitted to the École Royale des Beaux-Arts, the ninety-ninth out of a hundred students. This poor ranking was pure chance. Immediately afterwards, to the astonishment of his comrades, he rose to the top of his class, and in 1848 he obtained the second prize in the Grand Prix de Rome. His financial situation improved a little; once he entered the École Royale des Beaux-Arts, the city of La Rochelle and the departmental council of Charente-Inférieure gave him a pension of six hundred francs. The young painter used the opportunity to further his studies. From this day forward he was devoted to his art, to his painting; he consecrated body and soul to it. I have been able to read, thanks to filial piety, a journal that Bouguereau kept during this period, and its pages clearly depict his student life.2 One after the other, on every page, it contains intense and intimate confidences, philosophical and social reflections that are fascinating in their naive delicacy, as well as ingenious and original technical observations.

In a preface written on 23 March, 1848, the artist laid out his reasons for beginning the journal.

“I need to learn how to write, and that is why I have begun this journal. I trust it will serve another purpose — since an artist’s life is one of observation, and since memory often fails, I think it will be a very useful way to remind myself of forgotten facts and impressions. It will also keep me company and provide me with some distraction in my solitude. When I have laboured at a painting for a long time and am put off my work by fatigue and lack of success, it will comfort me a little to put some of my melancholy impressions on paper.”

He visits the famous monuments of Paris, the palaces and churches, to study architecture and decoration. The results of these studies inspire him to write the following: “Nature is really the only great master and it contains everything: colour, drawing, character, composition, etc. This is because the master of masters shows himself everywhere; nothing is neglected, nothing is useless, and everything bears the stamp of infinite power. So I will struggle along the road that is open to me, elevating my ideas to bring them a little closer to my model. The sight of a crowd gathered at church gave rise to these ideas. What a variety of characters and expressions, and yet they are of a whole.”

A little further on, on the same date, and on 25 March and 28 April, he gives himself some judicious and virile advice: “Before beginning to work, become one with your subject; if you do not understand it, look more closely or do something else. Remember that everything must be thought out first — everything, even the smallest things. Then think of the drawing, the colours, the arrangement; do not work without thinking through all of this as well, because nature, your only true master, has not omitted anything. Never depart from these principles, and you will will never be a mediocre painter .... Character is the result of thoroughly-understood truth. Seek it high and low! Various things have led me to believe, and rightly so, that the artist must find all the elements of the composition and the arrangement within himself. He must find his inspiration in nature but he must not rely on it, because we often have to wait until tomorrow to find what we needed yesterday.” This theory of artistic personality and autonomy that Bouguereau first sketched out as a young student at the École des Beaux-Arts will be developed further when he later becomes a master at that same school, and he will practice what he preaches for his whole life.

☞ If you would like to know when the complete translation of Vachon’s biography becomes available (as a printed book and an ePub), subscribe to the Obolus Press newsletter below:

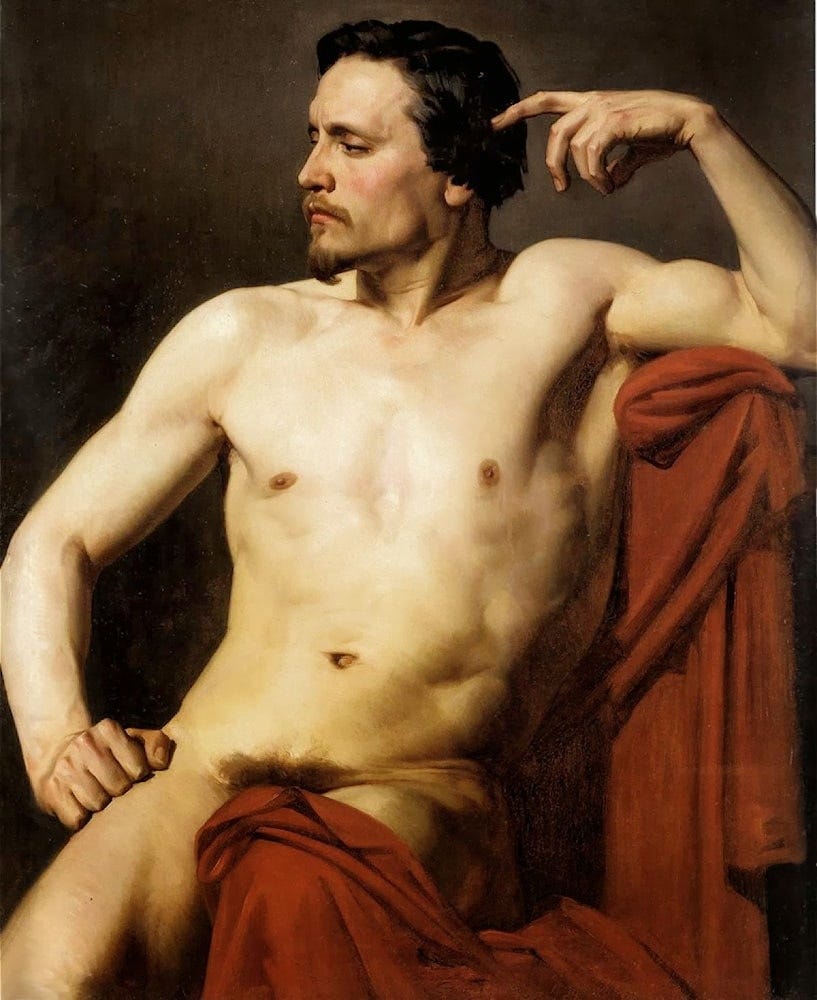

François Édouard Picot (1786-1868)