With Baudelaire in Brussels, #05

Baudelaire refuses an introduction to Leopold I, claiming that he is not dressed well enough to meet royalty.

To mark the 160th anniversary of Georges Barral’s trip to Brussels and his five-day visit with the poet Charles Baudelaire, I am publishing my translation of the first four days from his memoir on Substack. You can find the previous instalments here.

Nadar rushes off, stretching his long legs, taking me, Baudelaire, and everyone else with him. He seizes Baudelaire by the arm, but he resists, struggles, breaks free, and escapes, claiming that he is not dressed appropriately [to meet the King, whom we saw approaching in a carriage in the previous instalment].

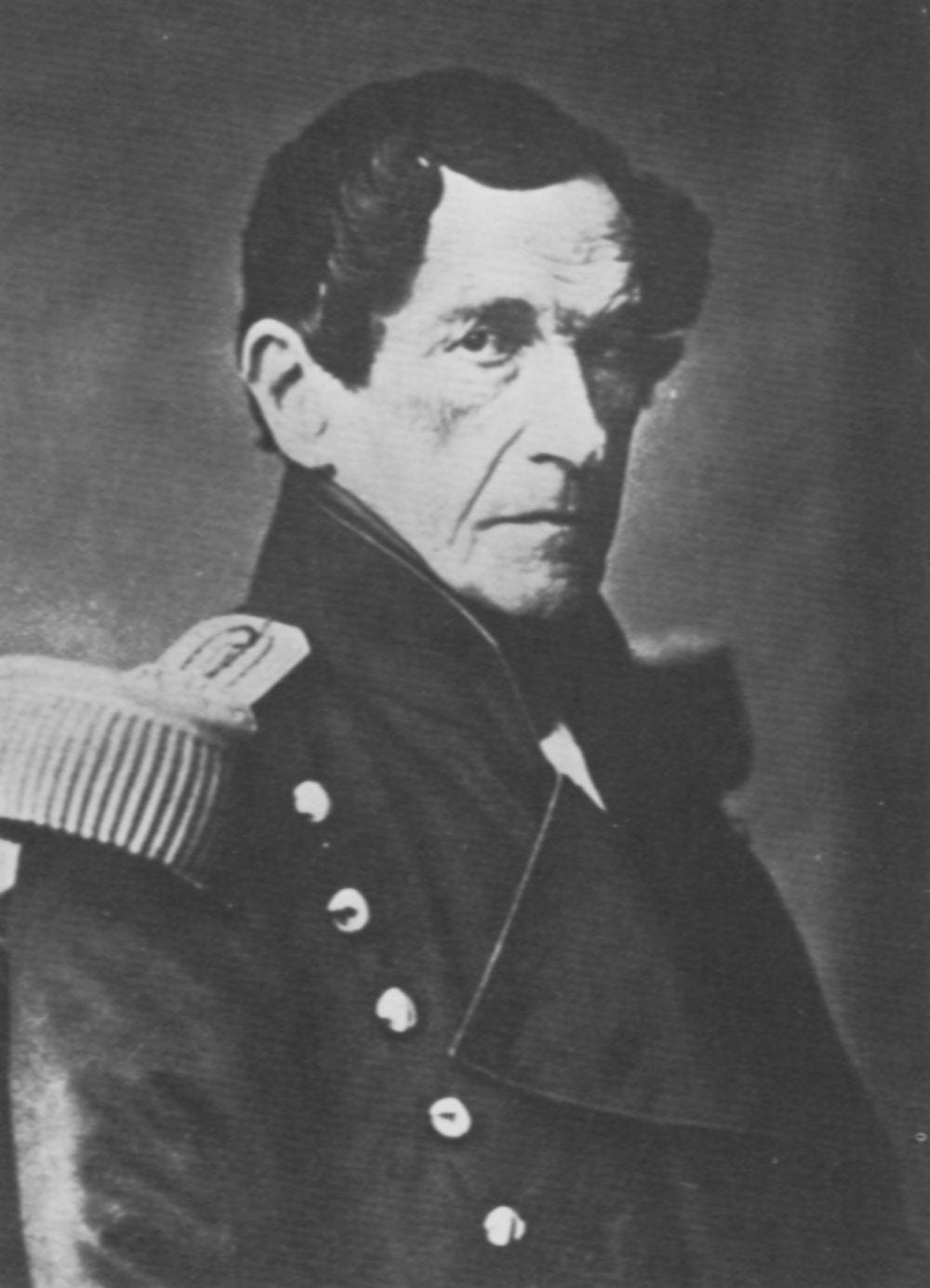

Then the King’s dashing and slender silhouette appears. Despite his age, Léopold I stands stiff and upright. His face is smooth, in the English fashion, and is lit up by two flame filled eyes. His smile is disdainful, sarcastic, and benevolent all at the same time. His hair is flat and black, and he is wearing a wig. He advances eagerly and offers Nadar his hand.

Nadar removes his hat, displaying his fiery hair, and bows deeply. He greets all of those in the monarch’s entourage, and offers to conduct the group to the platform. The King declines. “No, Mr. Nadar, I have come a little ahead of time to have the pleasure of speaking with you, to watch your final preparations before departure, and to have a lesson in aeronautical science.” “Ah, Sire,” replies Nadar in a lively manner, “I feel unworthy to give lessons to your Majesty!”

And so a brilliant conference takes place between the King and Nadar. Both of them are infinitely witty and equal in intelligence and nobility of feeling. They walk in small steps, while I keep back a pace. Nadar notices me and makes a sign. I approach with my hat n my hand, blushing and flustered.

“If you will allow me, Sire, I would like to introduce the youngest and most timid of my travellers,” says Nadar to the King.

“Welcome, young man. I like young and daring people. Sic itur ad astra! Rise to the firmament, but come back safe and sound. That is the best I can wish for you right now!”

I retire, walking backwards, bowing and babbling a few incoherent words as I go. I am embarrassed and proud.

There is frantic movement around the balloon. The King walks around it slowly, accompanied by Nadar. He asks questions, replies, and often smiles at his guide’s apt explanations. Noticing the rough canvas bags filled with sand that will serve as ballast, the King asks if they contain Belgian sand.

“If it is, Mr. Nadar, you must drop all of them before you leave Belgium. I am responsible for the integrity of the realm!”

“No, Sire. It is French sand!”, answers Nadar.

“In that case,” replies the King nimbly, “you are guilty of territorial intrusion!”

“Forgive me, Sire! But you know that the French always carry some of the homeland in the treads of their boots.”

Everyone bursts out laughing.

A telegraphic message arrives for Nadar. It is from Mr. Le Verrier, head of the Paris Observatory.

“In what direction will the Géant travel?” asks the King.

“At the moment the wind is coming from Russia. It is blowing strongly from the east on all of the northern region. We shall go towards the north west. To the United States, in other words.”

“And if the wind turns?”

“Well, we will remain in Belgium!”

“That’s that then,” concluded the King. “Don’t leave our frontiers, and in return for my visit today, come and see me at the Palais de Laeken.”

Nadar thanks him profusely.

“Really, Mr. Nadar, you are too kind to me!”

“Ah, Sire, Your Majesty, you will never know what high regard I – and all the people in France – have for the King of the Belgians.”1

With this confidence from Nadar, Léopold I withdraws towards the royal platform. The hour of departure is imminent, and everything is in good order. Nadar is holding a piece of paper in his hand, and calls for his companions. The balloon is balanced by systematically loosening the cords, but it does not move. It is too heavy. Nadar therefore names the travellers who must leave. The newest crew members are the first to be sent away, and the unlucky Baudelaire is numbered amongst them. He is sorely disappointed, and will hold it against his old friend.2

The aeronaut must cut short his farewells to his wife and child. He is the last to enter the gondola, and closes the door solidly behind him.

It is a solemn moment. Everyone falls silent. Then Nadar raises his cane towards the captain perched on the upper hoop, lifts his hat, executes a deep bow in the King’s direction and orders in a resounding voice,

“Let everything go!”

The balloon rises above the city. Remaining on the ground, Baudelaire waves ironically. “Have a good trip! Come back soon! Tomorrow, Tuesday, at noon, I will wait for you. We shall have lunch together at the Hôtel du Grand Miroir!”

“Tomorrow we will be in New York,” I reply dizzily.

To my embarrassment events will prove Baudelaire correct, but it will also prove to be the greatest honour of my life.

If you would like to support me as I ferry neglected artists and authors into English and back into print, I welcome small, one-off donations via PayPal.

A footnote from Barral reads: “This entire conversation is absolutely accurate.”

In a letter dated 30 August, 1864 and reproduced in Nadar’s Charles Baudelaire intime, Baudelaire offered to give up his place in the gondola to Mr. O’Connell, who let go of the cord on the day of the ascension.

You have to love the (over)confidence of that, "Tomorrow we will be in New York!"

Leopold I -- what a life!